|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From 'Port Desire'

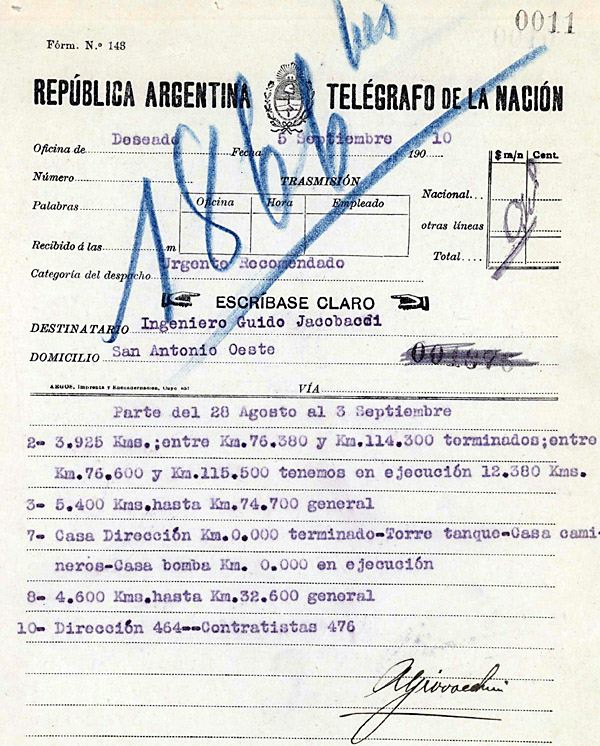

Rail rolled new for the Patagonian construction in 1910 is still in place at Fitz Roy station in 2011. A trunk line aiming for Lago Nahual Huapi The original intention was that this would be the main trunk route through Patagonia heading towards the far north-west where it would join the line from San Antonio somewhere near the present day resort of Bariloche. En route it would meet the Comodoro Rivadavia line on its way west to Lago Buenos Aires. There might also have been branches, perhaps to Trevelin or to Esquel. The various laws and decrees which led up to the construction and opening of this railway.

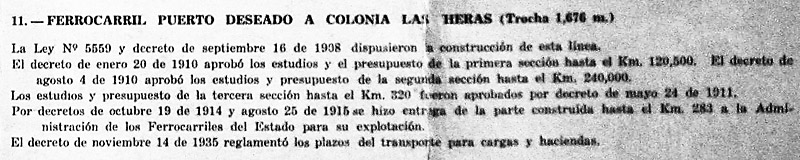

The work on the Puerto Deseado to Lago Nahuel Huapi (ie the place we now know as Bariloche) railway was under the direction of Ingeniero Juan Briano, whose boss was Ingeniero Guido Jacobacci based in San Antonio Oeste a good 450 miles to the north as the crow flies. Juan Briano disembarked from the Neuquén on 4 May 1909 and at once started work along with Captain Dodero, the ship's master, in order to determine a suitable location for the muelle which would be necessary for the unloading of all the materials necessary for the railway. On the 8th he sent the telegram below to Tulio Bertolans in Buenos Aires, who was presumably the recruiting agent for the unskilled workforce, asking how many men would be coming with the steamer Quintana and how many could be sent by the steamer Mendoza. Such rapid communication was made possible by the construction a year or two earlier of the telegraph line between Conesa and the lighthouse at Cabo Vírgines at the end of mainland Patagonia at the entry to the Straights of Magellan. Unlike later telegrams which were type written, this one is hand written.

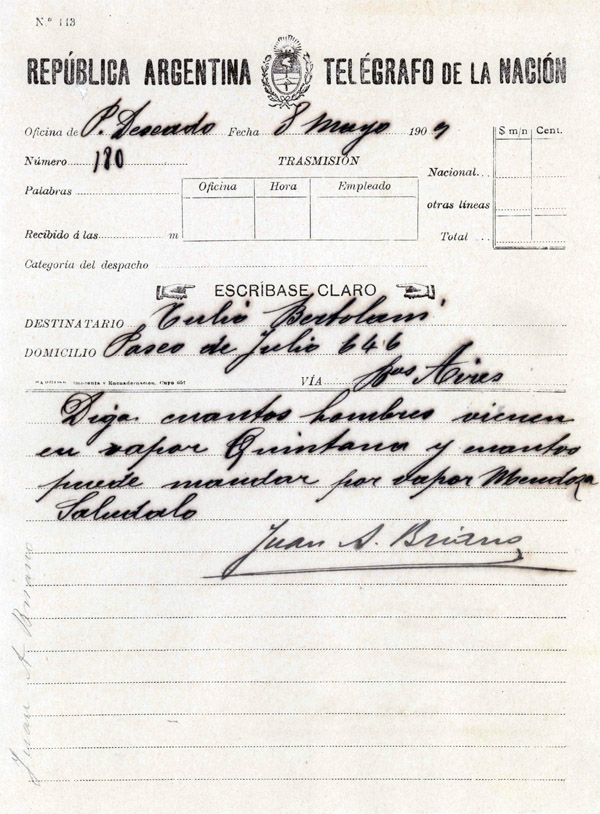

The telegram reads: However, even before setting sail from Buenos Aires, Ingeniero Briano had been at work as this telegram shows. It is asking the local police chief about the availability of firewood in the district, presumably to determine how much coal would have to be brought for such mundane purposes as cooking. It must be remembered that the construction of the railway involved introducing a workforce many times more numerous than the resident population, hundreds of miles from any existing established town of any size (Carmen de Patagones was probably the nearest).

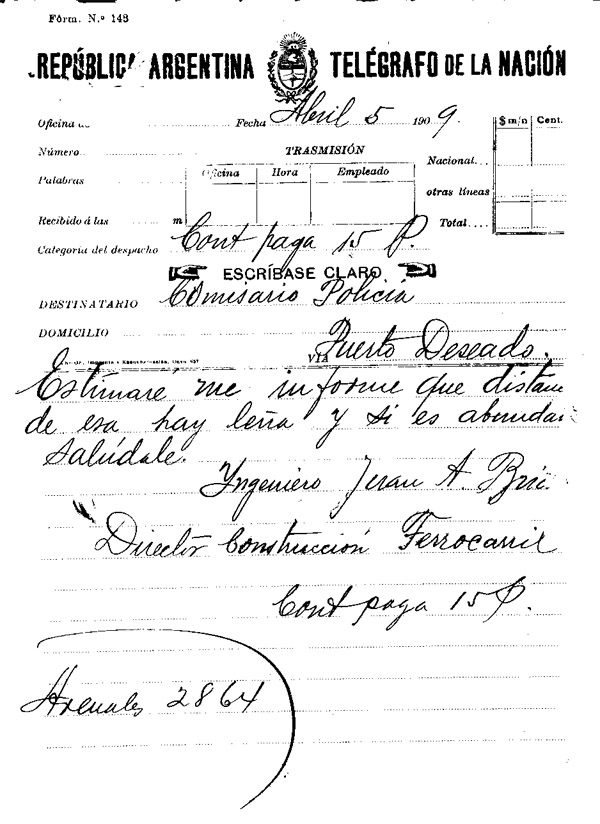

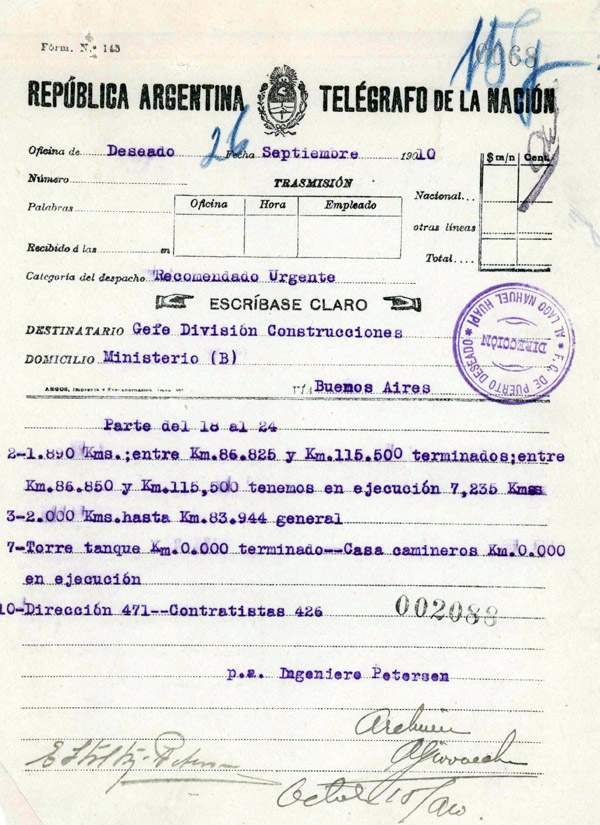

The telegram reads: Please advise me at what distance firewood is available and if it is plentiful. Greetings (signed) Juan A Briano Head of Railway Construction A telegram to Ingeniero Guido Jacobacci, the presiding engineer in Patagonia for the Ministerio de Obras Públicas, the progress made in construction during the week preceding 3rd September 1910. It should be noted that during this week 464 staff were directly employed and there were in addition 476 sub-contractors.

Direction of the work was taken over by Ingeniero A(ndriodante) Giovacchini in place of Ing Juan Briano quite early on. Such changes were common, as senior staff tended to be rotated among the various works in progress for the Departamento de Obras Públicas. Exactly three weeks later the weekly report was sent, but this time, to the Head of Construction in Buenos Aires and signed by Ingeniero (Emilio Stoltz) Petersen in the absence of Ing Giovacchini.

In September of 1911 a list was prepared of all staff engaged in the workshops function. This showed that there were 24 engaged in traction, including Alejandro Blane, inspector. This is the only name of clearly British origin in the list. There were 40 names listed under mechanical, ie the men who were assembling the locomotives and rolling stock, sent in knocked down format (for ease of unloading) and a further 36 under carpentry who dealt with the wooden aspects of the rolling stock, but also undertook the preparation and assembly of joinery work for all the buildings along the line. The complete list, in which the surnames may be studied to get an idea of where the men came from, is included as an appendix.

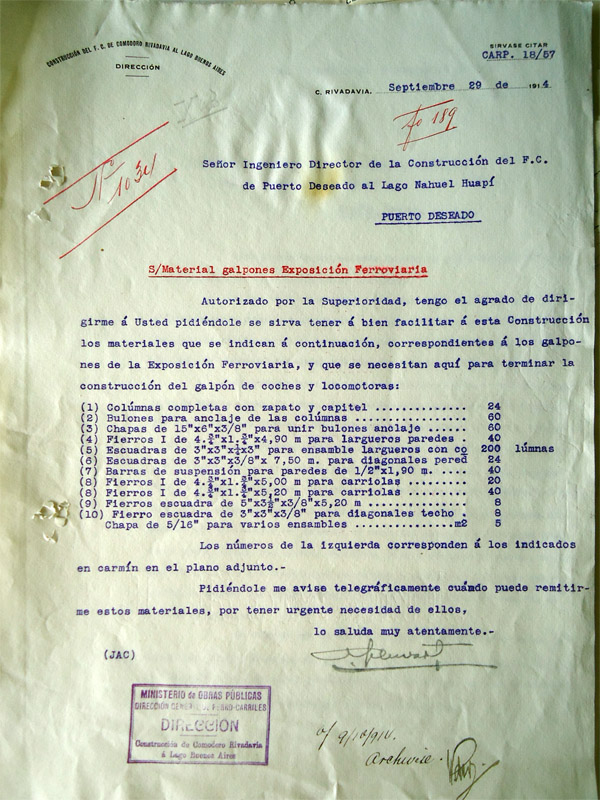

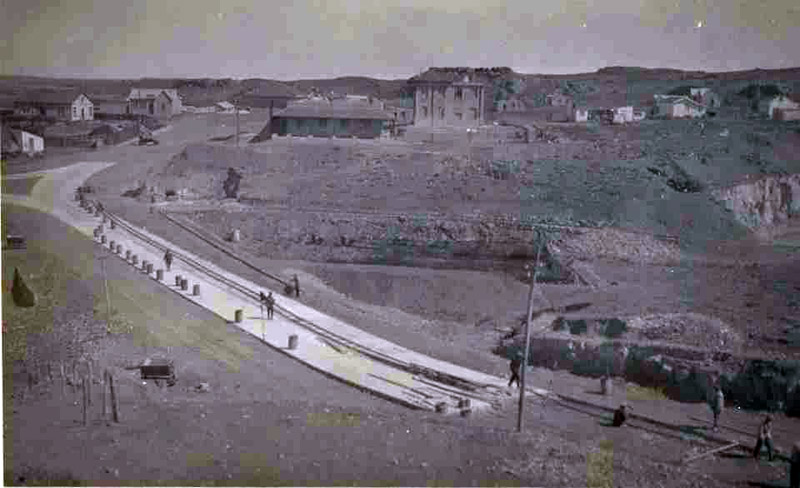

By 1914 economy was the order of the day. Various sheds had been erected in 1912 using material from the 1910 Centenary Exposition. However in September 1914, this letter, authorised from above, arrived from the Comodoro site asking for some of this material, specified in detail like a giant Meccano set, to be sent to Comodoro Rivadavia to allow the completion of the engine and carriage shed there. One assumes that the organisation, whether in Buenos Aires or San Antonio Oeste, knew that this material should be available in Puerto Deseado, either having been sent there in error, or clearly being surplus to what had actually been constructed. The surveys for the line were undertaken from 1908 to 1910. By a decree of January 20 1910 the first 120 km. was approved as an estimated cost of 21,210 gold pesos per km. In fact construction had started before that, in May 1909. The engineer appointed to oversee the main works was one Juan A. Briano. Sections of his diary have been published, edited by his son (1). Work in progress on the principal 'terraplenes', the cuttings and embankments, seemingly on the way up the hill from Puerto Deaseado station.

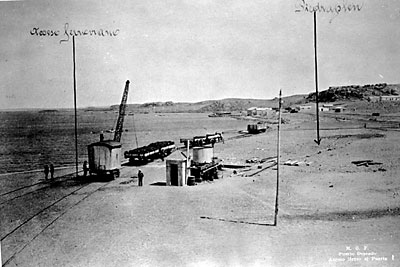

This is a view of the harbour branch nearing the completion of the works, but before the laying of the broad gauge track. [1567]

By the time war broke out in 1914 the railway had reached Colonia Las Heras, 178 miles inland. Worked stopped there never to be resumed. The financial and political reasons for this have been discussed in the first page of this chapter. By then a dozen or more locomotives and some hundreds of wagons had arrived, only to find themselves immediately redundant. Much of this equipment, listed on the next page, was second-hand from other Argentinean lines and in worn condition. I suspect that a lot of this was scrapped once it was realised that the line would go no further.

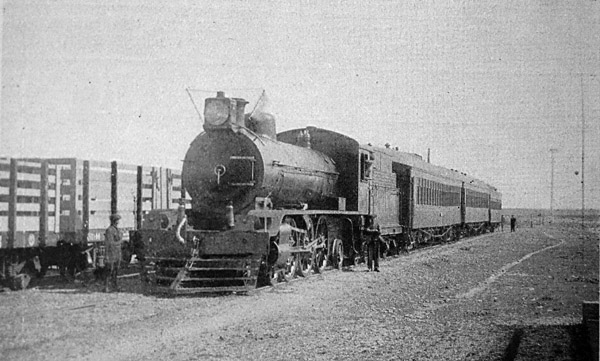

One of the FCE Haine St Pierre or Cockerill pacifics with a passenger train at Las Heras in the late 1920s, as pictured in the 1930 FCE passenger timetable booklet. The front two coaches are by Harlan & Hollingsworth, and the third is one of the ex FC Andino vehicles built by Lancaster. It was intended that the railway be extended to Lago Buenos Aires (480km from Puerto Deseado) with a connection to the Commodore Rivadavia line. However, it never happened.

Route details The picture shows the first short muelle, with a buffer stop clearly visible. The frigorífico at this point had its own narrow gauge line until about 1972.

Two photos follow showing more complex facilities at the port. The upper annotated one appears to have been taken from the roof of the goods shed in the lower one. The cars in the second picture suggest a 1920s date, and the railway tank wagon no. 28 is almost certainly one of the Ringhoffer built 1910 batch. These two pictures are reproduced by kind permission of the Archivo General de la Nación in Buenos Aires.

The tracks led east from the port, around the foot of the town. They then turned north into the main station site. The station was very substantially built in stone, for the builders expected this to be a major terminus of a 500 mile (800 km.) route down from the north-west. There was a loco shed, turntable and the necessary warehouses and other equipment, but no major workshop facilities because it was anticipated that locos and rolling stock could run via Lago Nahual Huapi to San Antonio for overhauls. Of course this never came about. The new station building at Puerto Deseado around 1912.

The turntable at Puerto Deseado with the loco shed behind. Whilst most mainline track survives (2001) many of the sidings at the terminus have been removed.

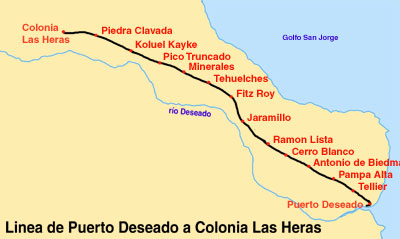

The region is extremely arid and like the routes of the other Patagonian broad gauge lines is mostly used for low density sheep-rearing. It climbs quickly from the coast to Tellier and sets off westward across an almost empty plateau rising very gently to Las Heras at a height of about 330m. (1,082 ft.) An itinerary of the places and features passed is on an appendix page.

Jaramillo station building above and water tower below. Jaramillo and Fitz Roy are the two main halfway stations and even they are adjacent to villages of only perhaps a couple of hundred people.

To the eyes of an outsider the emptiness of the landscape is the most striking feature. Reading a time-table one sees that in the 60 miles (100km.) after Tellier there are stations at Pampa Alta, Antonia de Biedma, Cerro Blanco and Ramón Lista before reaching Jaramillo and Fitz Roy. This seems reasonable - a station every 20km. It is only when actually traversing the route that one realises that that is precisely what was created - a passing loop and station house every 20 km. and absolutely nothing else in sight. In fact you can travel the full 100km. without noticing a single other house, except perhaps a sheep estancia or two visible through a pair of binoculars. Pico Truncado, at 202 Km. almost became a junction when a branch was proposed to the oil wells at Cañadón Seco. This might well have been the route chosen if the Puerto Deseado line had been linked up to the Comodoro Rivadavia railway, as was also proposed at one point. Las Heras station. A pacific is is on a train and a four-wheeled van is also present. Typical Patagonian farm carts are on the left. These, and the kerosene headlamp, suggest that this was certainly taken pre-war.

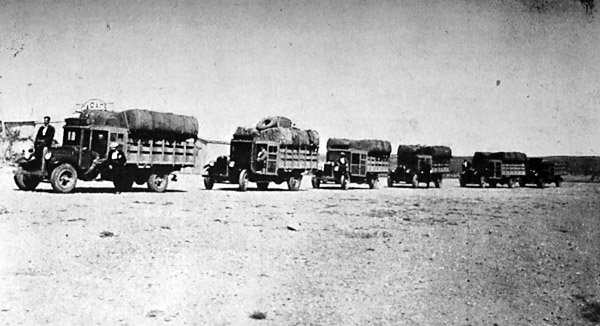

The track was laid with 8, 10 and 12 m. rails of between 31 and 37 Kg. per m. on wooden sleepers. The maximum gradient was 1.7% near the coast. The line was obviously single track throughout with fairly basic equipment. There were warehouses at four stations in total and a wagon weighbridge at Puerto Deseado. Water supply was from wells using windpumps. The opposition in its early days. A convoy of Dodge trucks arrives at Puerto Deseado from the west sometime in the 1920s (2). Wool bales are piled on several of the lorries.

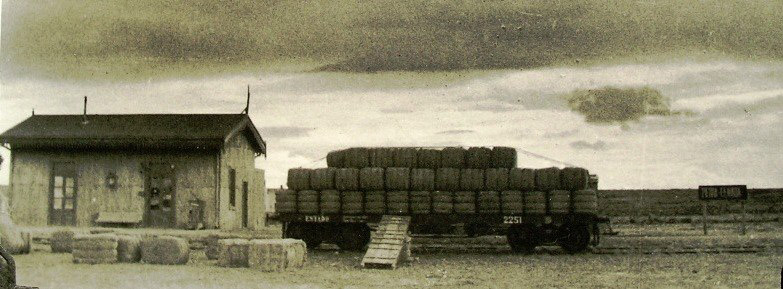

Views at intermediate stations are quite rare. Here is one at Pidra Clavada showing a bogie wagon, sitting on the secondary line, having been loaded with bales of wool. The ramp up which the bales were rolled has been slid away from the wagon (it's far end would have had to have been resting on top of the second layer of bales to allow the top layer to be loaded). The white splodge above the right bogie of the wagon is the PD in a circle logo. (2A)

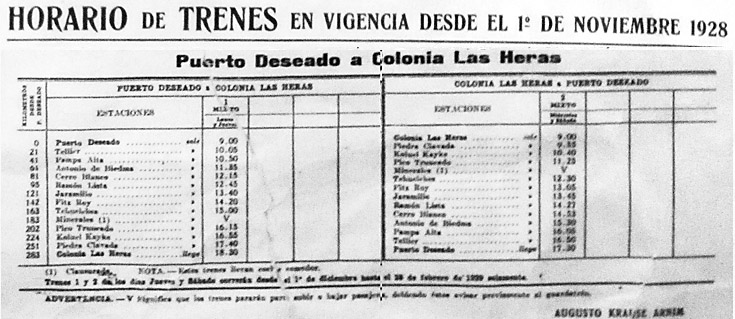

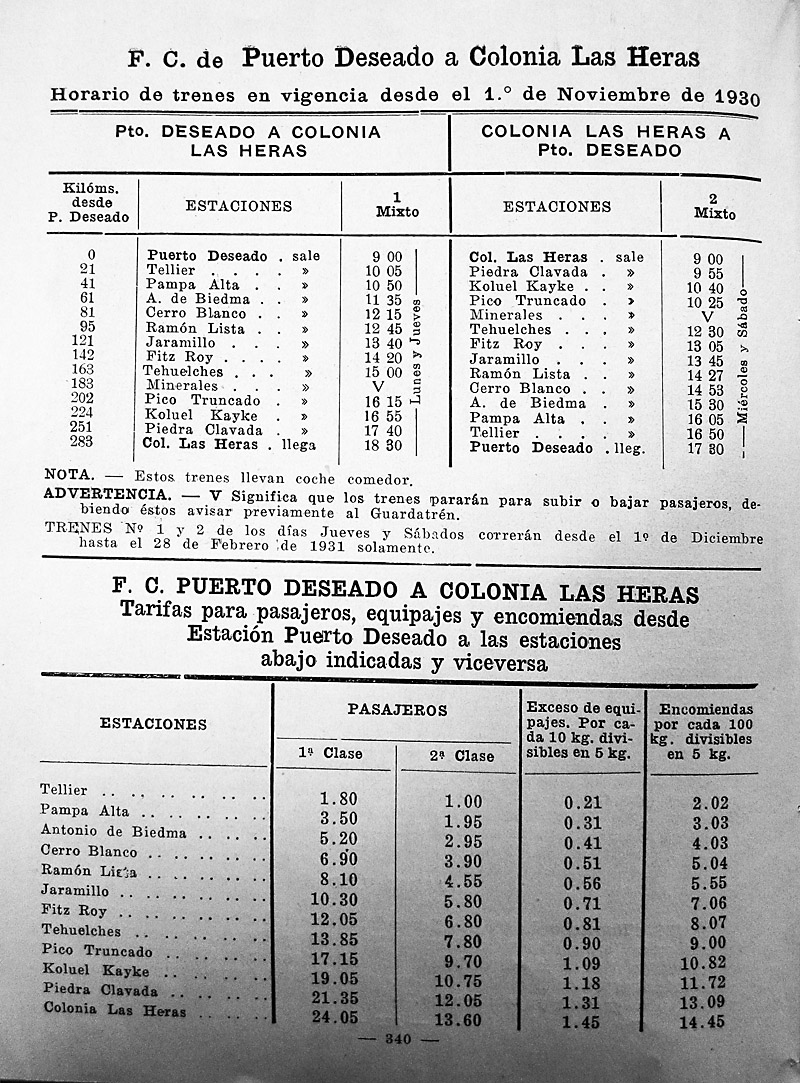

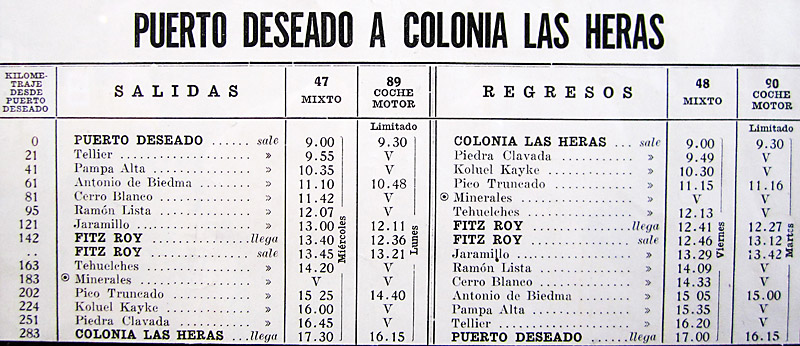

Gun-fights at the stations Operations Timetables The passenger timetables for 1928, 1930 and 1936 follow.

It will be noted that by 1936 one of the two weekly trains had become a coche motor.

The itinerario (working timetable) for 1946 has been studied, and also the public passenger timetable for late 1955 which is available on an appendix page. In 1946 there was solely one mixed train per week, departing from Puerto Deseado at 0900 on a Monday and reaching Las Heras by 1730 that evening. It returned on Wednesdays. By 1955 this had been replaced by a thrice-weekly coche motor, outwards from Puerto Deseado at 13.30pm on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, and in each case returning the following day. It should be noted that the coche motor took 5 hours 45 minutes for the uphill journey, compared to the 8 hours 30 minutes of the steam train. In both cases the downhill run was thirty minutes shorter. A perusal of the time table above will show that the trains (89 and 90) operated by the coche motor had a stop of 45 minutes at Fitz Roy in each direction. The Memoria of 1935 makes the reason for this clear. Starting in 1934, this was introduced to allow to local hotels at Fitz Roy to supply lunch to the passengers on the railcar; it was found to be much appreciated. [1610ka1] Rodney Long's 1926 report (4) lists the following figures for merchandise carried in 1915 and 1923:

Notice that there is relatively little livestock haulage. Mr. Long comments that the estancia owners continued to drive their animals on the hoof to the frigoríficos. A second table, below, shows that in its early years the line did sometimes get into the black, but as soon as road transport started to develop I suspect receipts must have plummeted.

The pattern through until the 1940s can be gleaned from the annual Estadística reports:

The 1947 history of Argentinean railways (5) sets out basic cargo and passenger figures for the early 1940s:

Freight traffic clearly rose substantially in 1942-4, possibly as a result of increased road fuel prices during a period of wartime fuel shortages. FC Patagónico The 1973 report (6) summarises freight traffic during the 1960s as follows:

It is obvious that goods traffic had fallen significantly since the '40s though the (admittedly poor) passenger figures had held up much better. The principal goods at the time was lead and zinc brought by road across the border from Puerto Cristal near Puerto Aisén in Chile. Wool and sheepskins was the second largest category. Passenger railcars by the 1970s were operating once or twice a week in winter and three or four times in summer, returning the following day.

Three of the tickets are for 'Clase Unica' the standard class of the railcars. The second one however is 'Primera Clase' . Whether the railcars had a small first class compartment or the irregular freights maintained a 1st class coach is not clear. The price has been left blank on the first two tickets, a wise measure in a country subject to high inflation and where the ticket might not be issued for several years! The third card has a fixed price and the 'use on day of issue only' is emphasised. This ticket looks almost like a day return that has been redesigned as a single. Finally the fourth one is an employee's privilege single for the whole length of the line. Special offers were not unknown as this notice of 29 January 1921 makes plain. The special return fare from any station within the special period was the single fare plus 50%. Miscellaneous For reasons unknown, an inventory was made in 1952 of the bedding, etc, allocated to the reserved coach. In March 1978, the inventory appears again giving details of where the various items were. In 1977, the Head of Works and Public Services of the Municipality wrote to the Station Master asking him for rainfall figures for Puerto Deseado. Two days later the reply was sent showing that the annual rainfall for the years 1972 to 1976 varied between 101 mm and 250 mm and snow between 1½ cm and 8 cm. One must assume that the Station Master's duties included rainfall measurement. Even though the line had closed in 1978, the ex Station Master at Puerto Deseado was sent instructions from Comodoro Rivadavia by Ferrocarriles Argentinos that the demolition contractor's men should be housed in the wagons which they had been sent to break up until the contractor's agent and railway representative arrived. Originals of all this correspondence is available in an appendix. All the items of correspondence come from the collection of Carlos Gómez Wilson, the last Station Master of Puerto Deseado. We are most grateful to him for allowing us to reproduce this material. A long-drawn-out decline and closure The telegram which announced the closure of the line (8). Since the final closure of the line in January 1979 there have been intermittent calls for its reopening. A detailed report was produced at one point, and a bimodal wagon was tried out on the track. Because of all the discussion the tracks have mostly been left in place, though often covered by sand or dug out to ease a farm crossing. Much of this track was second hand in the first place and it would not carry much after sixty years of neglect and another twenty of abandonment. However, perhaps its continued existence has prevented other landuses from encroaching on the trackbed! The view along the track - at Fitz Roy, December 2000.

Locos and stock Additional photos There is also a page by Humberto Brumatti dealing with the railway's postal service. Click on the link below: References 13-11-16

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chapter 4

The FCE broad gauge network

Main pages

Bariloche line rolling stock •

Com. Rivadavia line extra photos •

Pto. Deseado line extra photos •

Pto. Deseado line extra photos 2 •

Appendices

2 Chronology of Patagonian railway proposals •

3 Bariloche line route itinerary •

4 Com. Rivadavia route itinerary •

5 Pto. Deseado route itinerary •

7 Com. Rivadavia line loco list •

8 Pto. Deseado line loco list •

15 FCP working timetable instructions 1960 •

16 Report on construction 1912 A •

17 Report on construction 1912 B •

21 President Alcorta address •

23 Purchase of wagons decree •

25 Early Patagonian proposals •

26 Progress to Bariloche 1926 •

28 Restructuring report 1953 •