|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FCS diversification It is often forgotten that railways companies did much more than run trains. Commonly they operated ships, managed ports, ran bus services, and in some cases supplied the necessary water, electricity and other services to towns that had grown up alongside them. The FC Sud was no exception. It did many of these things in Bahía Blanca and was the obvious competent engineering contractor at hand when major works were required in the upper Rio Negro valley. Irrigation works for the Río Negro valley had been started in 1883, using convict labour from Fuerte Roca to dig a canal. A feature of many major Argentine rivers was their propensity to flood. The Río Negro and its sources, the Río Limay and the Río Neuquén were that way inclined. By Law Nº 3927 of 31 December 1898, studies were initiated into the river systems with a view to controlling flooding and to providing water for irrigation. These studies showed that a barrage was required across the Río Neuquén some miles above its confluence with the Río Limay. By Law Nº 6546 of 28 September 1909, the Southern Railway was engaged to undertake massive engineering works to provide irrigation along the north bank of the Río Negro. This included the Dique Cordero which took six years to build and diverted waters to a massive reservoir with a capacity to store 2, 000, 000, 000 cubic metres of water. This is what is today called Lago Pellegrini. (1) There is an account (in Spanish naturally) about the irrigation at <www.oni.escuelas.edu.ar/olimpi2000/rio-negro/fruticultura/historia2.htm> (1A) The branch line

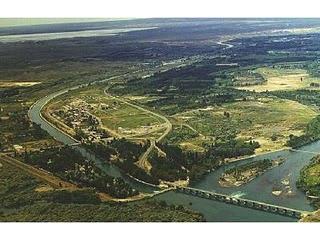

Branch lines are fairly rare in this part of the world. This one is the only one between Bahía Blanca to Zapala on the Southern or to Bariloche on the State. This aerial view was found in a blog whose name we have forgotten. It shows the end of the Cinco Saltos branch line at its terminus and is useful for location purposes. The S-shaped line curving away from the far end of the barrage is the modern road; to left of it, in the trees separating the road from the channel was the Fin de Rieles. From here it lead parallel to the channel to the right hand bend where it left the channel and finished up parallel to the new road. Estación Km 1218 was located just beyond the bridge over the channel.

This view was found in a newspaper article (Diario Río Negro of 25 June 2010). The engine is a class 8A 2-6-2T as used for shunting in the Bahía Blanca area; it is not possible to determine from the photo whether the fuel used is coal, asphaltite, crude oil, fuel oil or some other combustible. Behind it is a 60-ton brake van and a long train of vans. To the right are a couple of narrow gauge sidings of the irrigation maintenance railway, with an end view of two engines in the distance.

This photo, by Jorge Faye, shows the station building at Km 1218 in a shady spot in the early 21st century.

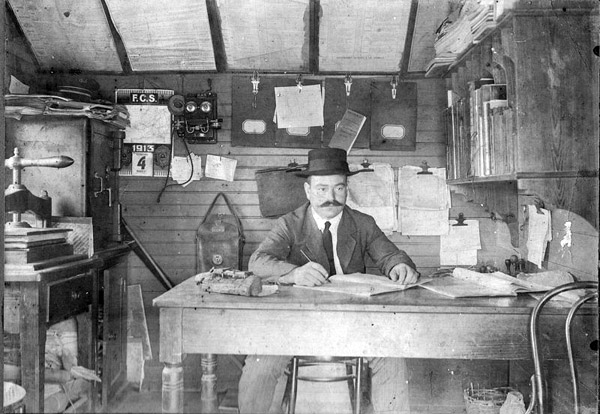

However, perhaps more surprising, is this view of Señor Jorge Faye's grandfather at work in his office at Km 1218. This rare view inside a railway office shows several interesting things.

• To the right of the 'phone are four clips boards, on the third one is hanging a copy of the working timetable (recognisable from its size and shape). The Cordero barrage, nowadays called the Ballester barrage, is located near the city of Neuquén. It's used to control the flow in the river and to store water for irrigation. This up-to-date view was found in <www.patagonias.net/IMAGES/Pictures/Dique-Cordero.jpg> (2) [This photo belongs to an unrelated website, which can be accessed directly by clicking on the image.]

The FC Sud was appointed to carry out the work of constructing the barrage and the construction of main network of irrigation canals. The construction of the barrage was clearly considered of national significance, so the President of the Republic, Dr. José Figueroa Alcorta, went to lay the foundation stone on 17 March 1910. Of course, he and his retinue did most of their travelling by train. The view below, taken at Km 1218, shows a special train, judging by the people including a number of ladies, standing for their photo, possibly the one associated with this visit. The formal opening of the branch was not until 25 June. The main canal, some 81 miles long, can deliver 72 m3/sec of water. To give an idea of how much this is, the Thames at London discharges an average of 65 m3/sec. From the railway point of view the picture is interesting as it shows the coach carrying tail lights, rather than the usual day-time discs, perhaps suggesting that it had been travelling overnight. The siding to the left clearly shows that it is laid using Livesey tortugas (tortoises). The FC Sud had been banned from using these in terms of their concession for the line to Neuquén and they were banned throughout Argentina by virtue of the Mitre Law of 1907. However from 1907, the company had been engaged in upgrading its track to 100lb rail on main lines and 85lb rail on secondary lines, no doubt releasing older serviceable lighter rail, laid with Livesey cups, to be used in sidings and the like.

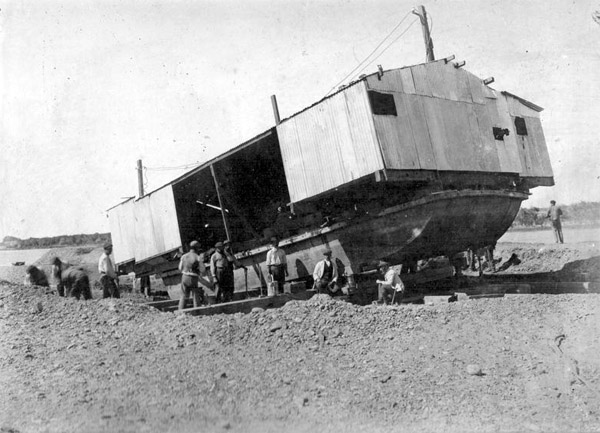

Ransomes and Rapier of Ipswich undertook the manufacture of the gates and other metal parts of the barrage. The barge, which is in the process of being launched, carries a large shed in which is the steam driven plant needed for the construction of each of the piers.

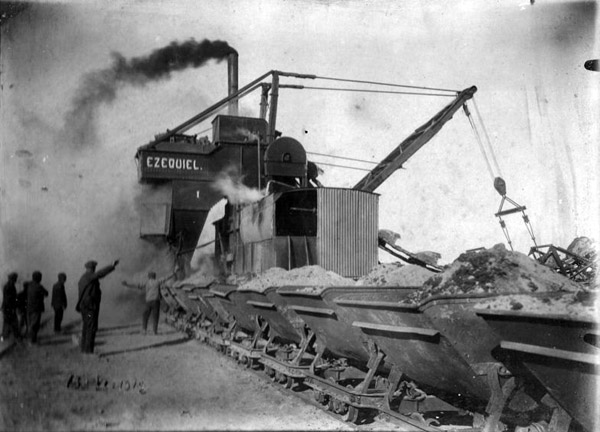

This view also provided by Señor Jorge Faye shows work ongoing on the main irrigation canal in 1912. Rather than employing armies of peones, the work is significantly mechanised with this steam operated drag line and temporary narrow gauge railway. The name Ezequiel on the drag line is no doubt a tribute to Dr Ezequiel Ramos Mexía who was instrumental in promoting the irrigation works.

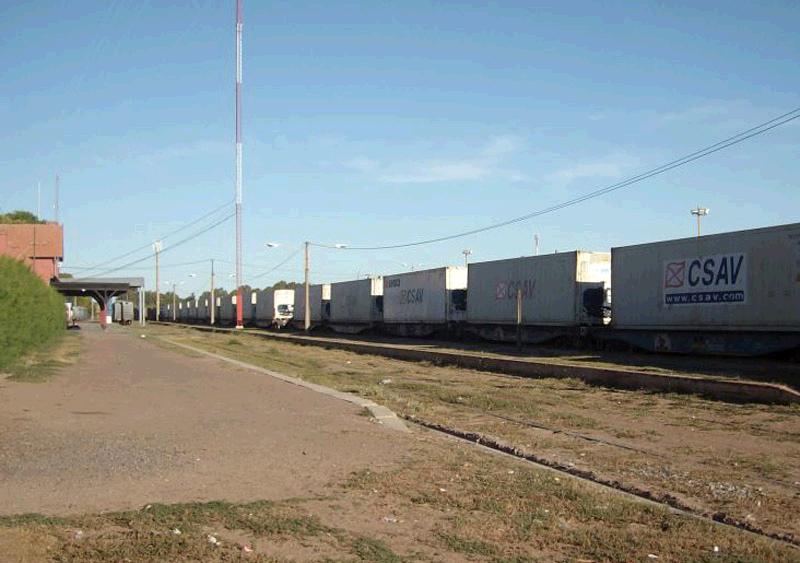

In the oilfields Colonia Regina de Alvear The process was much the same in most such settlements. In this case a development company was formed which purchased, in some areas land was granted by the Government, some 5, 000 hectares (approaching 19 square miles) of land provided with primary irrigation. The company then started to develop the first 1, 300 hectares by dividing it into 130 plots of 5, 10 or 15 hectares, fenced it, provided roads and a network of secondary and tertiary irrigation canals. The company promoted a ladies' committee to build the church. The village associated with the development, in addition to the church, was provided with a school, sub-police station, post office, recreation centre and an electrical power station. The Southern Railway's contribution was in the form of a new station which included a large double-ended goods station for the transfer of agricultural products. You can read the complete text of the chapter translated in an appendix. Click here to go there. (8) Fruit for the World From the 1920's agricultural production in the smallholdings tended to start to concentrate on growing fruit for export. In 1928 the Southern Railway created the AFD or Argentine Fruit Distributors. This undertaking developed the picking on individual smallholdings and arranged its transfer to packing stations strategically located in the upper valley where the fruit was graded and packed ready for transport. These packing stations were naturally incorporated into goods stations of the Southern Railway located at Cinco Saltos, Cipolletti, Allen, J J Gómez and Villa Regina (Colonia Regina Alvear as was). (10) From these points the fruit was whisked by train in ventilated vans to Buenos Aires for export to the Northern Hemisphere. This traffic grew over the following twenty years, demanding the use of engines of significant capabilities. Engines of classes 15A and 15B were often engaged on this traffic and became known as fruteras ˜ fruiterers. This is a press view of the first fruit train (February 2013) from the Upper Río Negro valley to Ingeniero White since about 1983. The fruit is now conveyed not in vans, but in refrigerated containers, which are loaded aboard ship without emptying. The view appeared on Ivan Juarez's Facebook Page.

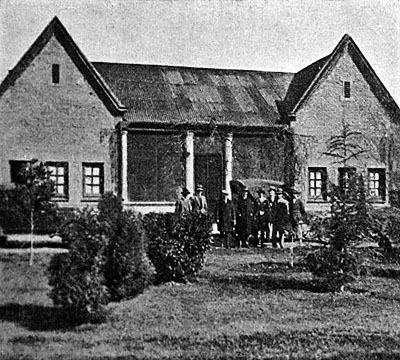

The Cinco Saltos Experimental Station This is the administration building of the railway's small holding. (11B)

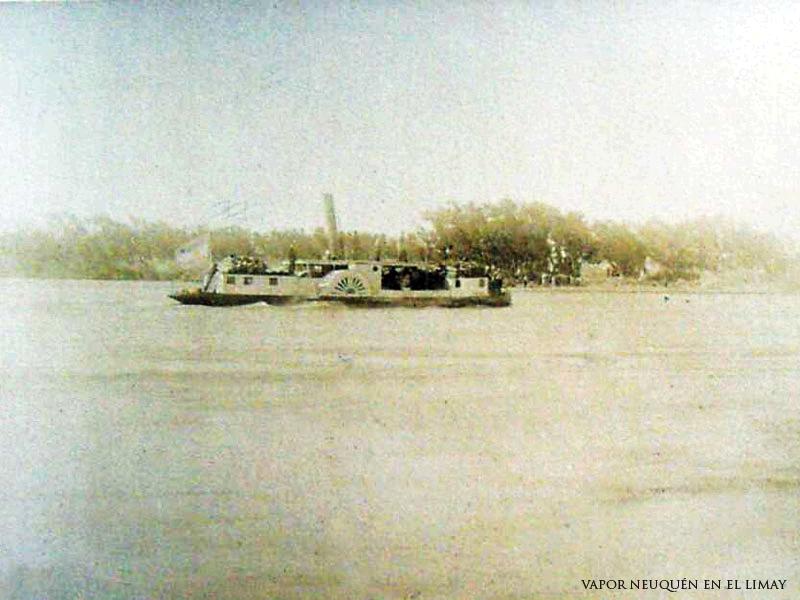

In 1902, the Rev Alejandro Stefenelli, a Salesian priest, established an agricultural school for orphans. In 1963 these two establishments came together to form the Estación Experimental Alto Valle (the Upper Valley experimental station) which is nowadays located in Guerrico. There's an account in Spanish of this establishment at <http://www.inta.gov.ar/altovalle/institucional/historia/historia.htm> (Not available in April 2012) (12) Navigation on the Río Negro The first river service between Patagones and Choele-Choel was started by the vessel Choele-Choel (ex Marianita). (15) The first steamers (paddle vessels) built specifically for use on the Río Negro were the Río Negro and the Neuquén. They were built by Cammell Laird of Birkenhead with yard numbers 469 and 470. They were dismantled and despatched in small bits for re-assembly in Patagonia. (16) This is a view of the small steamer Río Negro moored in front of Patagones in 1882. The view was found in the web site dealing with the centenary of the city of Neuquén. I think it is one of the two vessels mentioned above. (17) [This photo belongs to an unrelated website, which can be accessed directly by clicking on the image.] Views of the small paddle steamers are uncommon, even more so above Confluencia. This view, of the Neuquén, is said to show it on the Limay, was found in Soldados Digital, an army web site. Why it appears in this location may be explained by noting that, when General Roca was leading the Conquest of the Desert, logistical support was given to the troops by this vessel and its sister, the Río Negro.

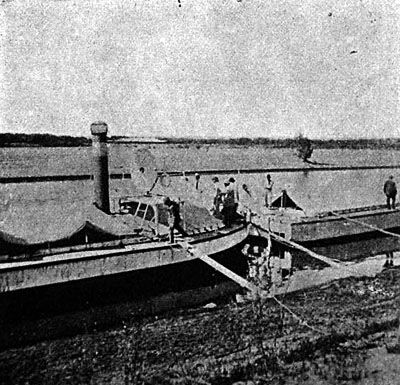

The Argentine Navy continued to provide the service with various craft until 1890, when the service was privatized. In 1902 the FCS bought two cargo vessels from Yarrow of Poplar (London). They were called the Limay and the Neuquén with yard numbers 1135 and 1136. Their principal dimensions were: length 85 feet, beam 16 feet, draft (fully laden) 28 inches and empty 11 inches. As with the Cammell Laird vessels, they were sent dismantled to Argentina and forwarded by train to Chelforó, where they were re-assembled. (16) On 19 October 1903, the FCS announced the starting of a river service on the Río Limay. This service was suspended in December 1905 for lack of water in the river and was never restarted. (18) Up till now we haven’t been able to find good photos of any of these little steamers. This one is in Coleman’s book; the caption indicates that the two of them are moored at Choele-Choel. The gang-plank lands on the deck next to the bridge in front of the funnel. (18A)

Trippers aboard the small steamer Neuquén. The photographer is looking forwards and one can see the totally open bridge. (19)

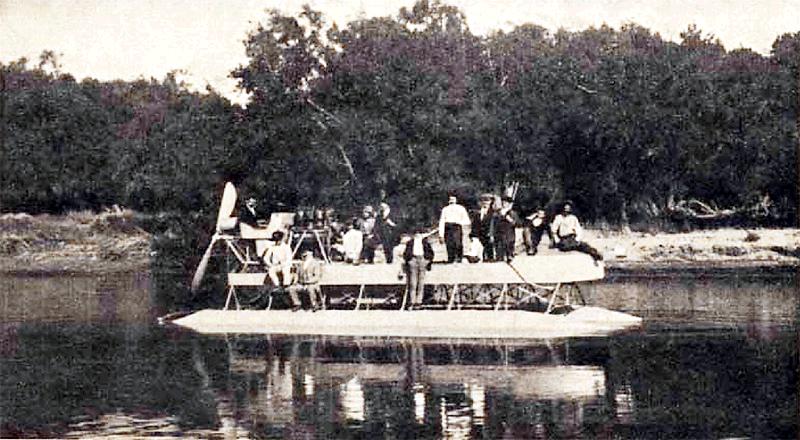

A water-borne service continued until 1949 on the Río Negro, most of the time solely downstream of Choele-Choel. (20) In January 2010, navigation on the Río Negro was formally drawn to a close with the publication of a report by the Director General of Cadastral y Territorial Information for the Province of Río Negro concluding that the river was not now legally navigable. While this may seem to be an academic exercise, it is in fact of considerable importance in terms of the constraints and obligations on riperian landowners and the provincial government's duties and responsibilities. (22) There is a web site (in Spanish) at <http://www.lagalerapatagonica.com.ar/historia_de_la_navegacion.htm> by Miguel Bordini which deals with this topic in greater detail. (21) Link currently (January 2011) unavailable For something completely different: here is an 'airboat', a catamaran driven by an aircraft engine and airscrew.

We thank Dan Buck for drawing this strange craft to our attention. The information which follows comes from a newspaper article in La Mañana Neuquén in 2012. An Italian immigrant called Remigio Bocci, later corrupted to Bosch, settled in Confluencia about 1900 where he set up a business as a blacksmith. He made his income repairing the carts which were the only means of goods transport at the time. In 1914, no doubt aware of the failure of the FC Sud to establish a viable steamer service on the Río Limay, he invented this airboat to get over the difficulties of the shallows and rapids in the river. It was powered by a 60 hp petrol engine with a nine-foot diameter propeller and on a trial run with 28 passengers managed 15 kph up the Limay. However it did not prove practicable for the conveyance of goods and he kept it as a personal runabout. In 1916 a group of German sailor prisoners-of-war escaped from Isla Martín Garcia (in the delta of the River Plate) and got to Neuquén unrecognised. They stole the airboat with a view to going up the Limay to Bariloche and thence across Lago Nahuel Huapi to seek refuge in Chile. However the local police chief got wind of what was happening, pursued them by land and recaptured them. And that was the end of the airboat. Sources: 21-7-2015 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

Chapter 3

The BAGSR's route to Neuquén