|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

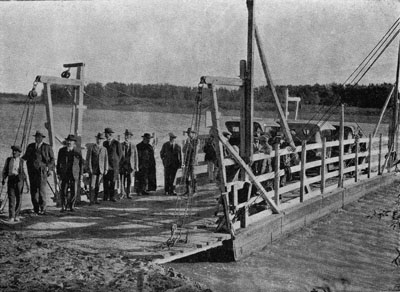

Traffic and timetables The Train Service The temporary terminus, until the completion over the river and into Neuquén, was equipped with a triangle for turning complete trains which had been installed for the opening of the line on 1 June. The Southern Railway were slightly disappointed with the traffic results in the first year or two, but from 1903 onwards regarded them as very satisfactory for the year 1903-04, some 43, 840 passengers of first and second class were carried, along with 788 tonnes of parcels, 36, 806 tonnes of goods, 439 horses, 3, 488 head of cattle and 148, 195 sheep. (4) The nucleus of a village had grown up around the original temporary terminal station which had been called Confluencia. With the closure of the station the villagers felt cut off and petitioned the railway to re-open it to provide a means of crossing the river Neuquén. It was reopened on 15 May 1904 as Limay and renamed Cipolletti in 1910. In this view dating from 1910 one can make out the railway bridge in the right background. In addition to rail traffic it was used by pedestrians. However, road traffic still had to cross the river by ferries such as this. I'm not clear how it was propelled, but I suspect that it may have been a "chain ferry" attached to a rope anchored on each side of the river. (1A) [This photo belongs to an unrelated website, which can be accessed directly by clicking on the image.] This modern view taken inside the bridge shows that it is not suitable for pedestrians as it was in past times. One can see the road bridge alongside it. (2) [This photo belongs to an unrelated website, which can be accessed directly by clicking on the image.] How to make passengers' travels confusing A new station was opened about 1908 to serve the new village which was growing up opposite the island of Choele-Choel. This station was given the name Darwin. Thus the strange situation pertained that the station for Darwin was called Choele-Choel and the station for Choele-Choel was called Darwin. Matters were put right by a government decree of 18 May 1911 which swopped the two station names, thus making the village and station names coincide. The line ran along the north bank of the Río Negro. Naturally there were establishments and villages along the south side. Their connection to the railway was across the river using ferries such as this. They were propelled by a winch working on a steel cable stretched between the two banks. (3)

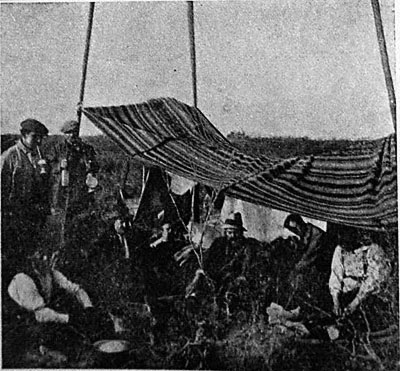

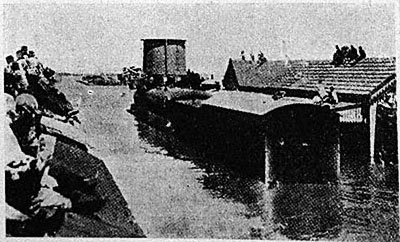

The Rio Colorado flood There were also signs that there would be floods on the Río Negro. The governor of the territory of Neuquén telegraphed the District Traffic Superintendent of the Southern Railway at Bahía Blanca. At that time the District Traffic Superintended was the redoubtable Arturo H. Coleman. He at once organised a relief train, of twenty bogie vans and two open wagons which conveyed four rowing boats. Other railway officers involved were Messrs Nelson and Field of the Engineer-in-Chief's Department and N G White the Traffic Inspector. One assumes that the train also conveyed one or more squads of labourers. It would appear that they also took along a correspondent from the La Nación newspaper. Arthur Coleman (with black hat), traffic superintendent of the Southern Railway meeting William Harding Green, traffic superintendent of the Bahía Blanca North Western Railway in 1925. (3A) [This photo belongs to an unrelated website, which can be accessed directly by clicking on the image.] When the train reached Buena Parada, which was the village about 5km from Río Colorado station, they found the station crowded with refugees from the flood. These were at once got on board, and the train took them on to Río Colorado which stood bit higher. The train then went on up the line to answer the call of Governor Eduardo Elordi, but, some 15 km on, was stopped by the flood waters, which rapidly rose up the sides of the wagons. The staff had to launch the boats and rowed to a nearby knoll which was now an island. They eventually got by to Río Colorado by the boats. We are fortunate that Arthur Coleman was an enthusiastic photographer. The following photos were taken during his adventure in the great flood. (4) The flood water reaches the rails and stops the train. The photo was taken from the cowcatcher (= 'pilot' in US parlance) of the engine.

The shelter on the hummock where they stayed for almost a week.

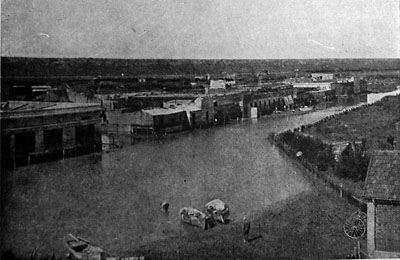

This is what they saw on their return to Río Colorado station.

The main street of the village of Río Colorado once the waters had started to recede.

After the flood the Southern Railway engaged an engineer, S Blencowe, to investigate the circumstances giving rise to the flooding. They also had to rebuild 100 km of track and embankments damaged by the flood. It is possible to read various descriptions of the catastrophe. Click here to read a recent account in the daily newspaper Río Negro. (5) Click here to go to another version in the daily newspaper RíoNegro. (6) Links currently (January 2011) unavailable. A full description of the disaster is contained in Arthur Coleman's autobiography, chapter 5 of which is available in an appendix page. The relevant section of William Rogind's book is also available in translation. The aftermath of the great flood, a stranded train on January 2nd 1915.

A Rotary Club excursion at Plaza Huincul station in April 1933. Sources: 22-7-15 |

|||||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

Chapter 3

The BAGSR's route to Neuquén