|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Westwards from Bahia Blanca In the Beginning The only mechanised transport were a number of small river steamers. The Río Negro never developed as a major navigable waterway. Road vehicles for domestic transport may seem a little primitive. This scene would not have been out of place a hundred years earlier. Unlike the four wheeled covered wagons of the prairies of the United States, the corresponding vehicle in Argentina was generally two-wheeled. This photo comes from the Neuquén provincial website.

A Strategic Railway The Argentine Government saw the urgent need for a strategic railway capable of carrying troops into the area rapidly. In mid 1895, the Chairman of the local board of the Southern Railway was offered a deal, basically to provide the necessary line for the government in return for various concessions. The railway had carried out a traffic survey previously and had concluded that there was insufficient potential traffic for them to invest in that area. It may be that they had also carried out preliminaries studies into the routing of such a railway. Consequently, initially, the company was decidedly lukewarm about the project. However, the Government, represented by Dr. Benjamín Zorilla, persisted and, eventually, an agreement between the Government and the Southern Railway was signed on 16 March 1896. Critical points of this agreement were: The Government had granted a concession to McPhail & Co for a line from Bahía Blanca to Chos-Malal (some distance beyond Neuquén), then the administrative centre of the territory. and never served by railway on 26 June 1895. They subsequently stood down from it in favour of the Southern Railway in the interests of national defence. By July 1896, plans for the first 175 km of line, taking it over the Río Colorado and just into Patagonia, were presented for approval. The plans for the remainder of the line were submitted and subsequently approved on 24 March 1897, meaning that the line was due to be opened at the end of March 1899.

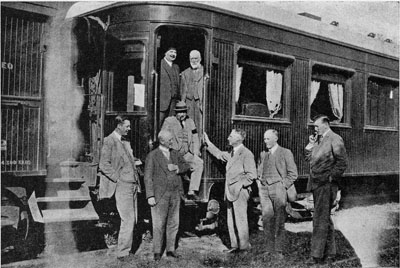

Directors and senior officers of the FCS stand at the doorway of an inspection saloon during the return journey from a tour of inspection of the Neuquen route. In the doorway are Colonel Woodbine Parish, Sir Henry Bell and Mr. Arthur Coleman. The authorization for the opening of the first section of line to Río Colorado (Km 171.5) was given on 13 September 1897, goods and passengers being conveyed by the trains carrying construction materials for the rest of the line. The authorization for the opening of the second section, a further 178 kilometres, to Choele-Choel, on the Río Negro, was provisionally granted on 30 June 1898. A short third section of 56 kilometres to Chelforó was authorised on 31 December 1898, while the fourth and final section was authorized for opening on 30 May 1899 with a formal opening arranged for 1 June. The crest of the Buenos Ayres Great Southern Railway or 'FC Sud'.

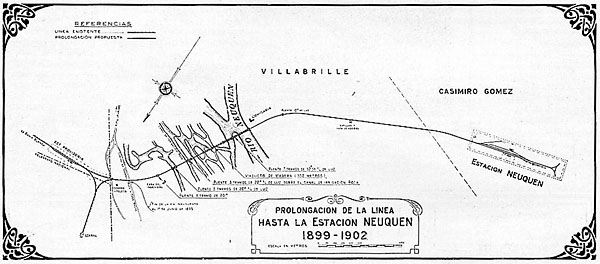

A Grand Opening On the thirty-first, three special trains left Constitución station in Buenos Aires conveying the president and all the important guests for the opening ceremony which was to have been held at the end of the line with a grand banquet in a giant shed at Fuerte Roca. They had a stop-over at Bahía Blanca and set off again before dawn. However! Things were not to be. The Río Negro had been rising for a few days and as the trains were proceeding along the banks of the Río Colorado, word came that the line ahead had been flooded beyond Chelforó. The president was keen to press on. At Choele-Choel the extent of the floods could be seen. The three trains were stopped at Chimpay. There, with the three trains on adjacent tracks, an impromptu opening ceremony was held with appropriate flowery speeches. It was thought wise to retreat quickly. The first train away carried the Traffic Superintendent of the Southern Railway, accompanied by a squad of surfacemen. The three special trains then followed at twenty minute intervals. The flooding had already reached the line in places between Chimpay and Choele-Choel, but they got through safely, and all met up again at Fortín Uno (in the valley of the Río Colorado and well clear of the Río Negro valley), where there was an impromptu dinner in the dining carriages. After that, the trains set off again for an uneventful journey home. The complete text of the Chapter in Rogind's book (2) which deals with the construction of the line is available in translation in an appendix page. Señor Arthur Coleman, Traffic Superintendent of the FCS in Bahía Blanca, also wrote of the construction in Chapter 2 of his autobiography (3), also available in an appendix page. Some things are dealt with in more detail than in Rogind's book. Over the Neuquén Strangely, the map below is up-side-down, with north towards the bottom left. The line from Bahía Blanca comes in on the left to the station now named Cipolletti, before crossing the river into Neuquen proper.

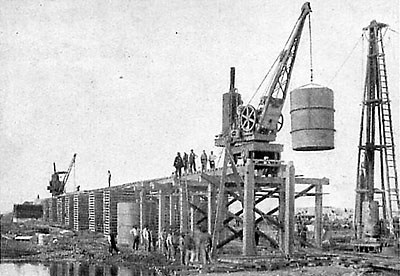

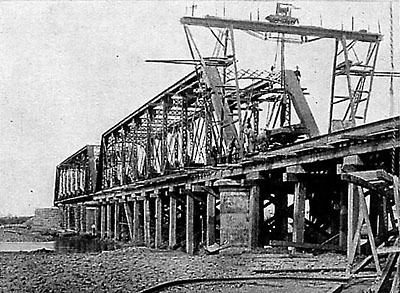

The bridge comprises some seven spans of 52.20 metres each, plus a timber trestle approach viaduct 352 metres long and several smaller bridges on the approach viaduct from the east. The bridge was designed by consulting engineers in London and was not untypical of the period. However, it did provide a first in Argentina in the use of compressed air for the construction of the foundations. During construction there was another major flood, of which there was advanced warning from further up river. Nevertheless, at one point workmen had to climb on to the tops of wagons standing on the embankment to stay out the water.

Two stages in the construction of the approach trestles.

The formal load testing in the presence of the Government railway engineers took place on 12 July 1902, and authorization by decree to start a public service was given on 12 July. With the opening of this extension the original temporary station was closed, but not dismantled. The seven main steel spans, shortly after completion, and with an interesting looking 'ogee' saddle tank on the right.

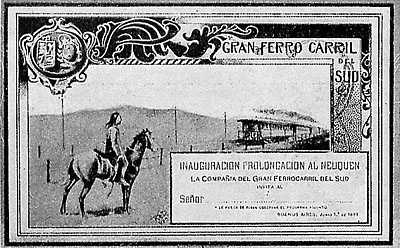

During the period of the construction of the bridge the train service from the east comprised two passenger trains per week plus one goods train. An account (in Spanish, of course) of the opening in 1902 is available in the daily newspaper Río Negro. (4) Click here to go to it. The invitation card to the grand opening into Neuquen.

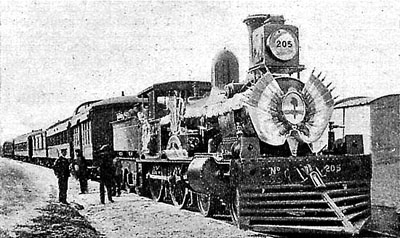

The decorated inaugural train, headed by 4-4-0 no. 205.

A ticket for the train.

The medal issued to commemorate the event.

It is interesting that in the account of this line up to this point there is no reference to outside parties other than consulting engineers for the design of the bridge. The inference is, then, that the whole of the engineering and construction of the line was undertaken by staff directly employed by the Southern Railway itself. Rogind's Chapter 30 covers this and the work further west. As before a translation is available in an appendix page. I think that this view was taken from the Neuquén side of the river in 1920. On to Zapala

References: 25-12-08 |

|||||||||||||||

Chapter 3

The BAGSR's route to Neuquén

Main pages

Appendices