|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Attempts to cross the border The Trasandino Sur This proposal was presented to Congress in August 1906 in preference to one submitted by Messrs Sigifredo Nathan & Co for a similar line. This lead to law No 5535 of 25 June 1908 which established a priority for the construction of a line to Chile via either the Pino Hachado or Lonquimay passes. This was later amended to be rather less specific. (1) The full text of the law is available in Appendix 21. What is noticeable is the brevity and lack of specificity of it. It is without limit of time, and so it was used as the authority, nearly a hundred years after its promulgation, for the construction of the extension to Zapala Cargas. Shortly afterwards the Southern Railway started construction of the line at Neuquén. This line soon reached Zapala, some 115 km from the frontier, at which point the railway were unable to raise further funds for its construction. On the Chilean side a length of 110 km remained to join to the end of the Southern Railway. As this was 1914, perhaps the onset of the Great War had something to do with the money difficulties. Thanks to Héctor Guerreiro we have this commercial view of a passenger train arriving at Zapala, the date unknown, but could be in the 1930s.

Zapala station, looking west, in June 2011.

This section of line had the steepest gradient on the whole of the Southern Railway, 1 in 80 (1.25%). The average gradient from Neuquén to Zapala was 1 in 220.

The Argentine government railway administration took over the promotion of the line and decided to find another route which would involve a lower summit of the order of 1, 200 metres above sea level but involving a tunnel 1, 000 metres long. A commission to do this was appointed in 1922. At the same time an agreement was made with Chile, but not ratified by the Argentine side, whose first clause was in the following terms: 'The Governments of the Argentine Republic and the Republic of Chile have reciprocally resolved on the construction of two railway lines joining the two countries without trans-shipment: first, in the north, the Argentine city of Salta with the Chilean port of Antofagasta* , and second, in the South, the Argentine port of Bahía Blanca, by the extension of the Southern Railway at Zapala (Argentina) to a junction with the southern Chilean network. The two lines could come into service within three years of the date of this agreement. They believe that the time has come to define norms which define and orientate inter-ocean policies.' (2) * Note: ˜ This line is the well-known Ramal C14 which still functions as the world's third highest summit. Passengers can enjoy the delights of part of it travelling from Salta on the Tren a las Nubes. This line is operated by adhesion with a ruling gradient of 1 in 40 (2.5%) and a minimum radius of curve of about 6 chains (120 metres). A map found in the Archivo General de la Nacion in Buenos Aires is illustrated below. The rail route starts as a solid line, meaning firmly agreed, at the bottom right, but then soon turns into a dashed line, which the key suggests is proposed but not yet firmly agreed. This heads north-west from Pavia bypassing Las Lajas, and then turns west and into one of several parallel valleys, separated on this map by heavy lines along the watersheds. This takes it up to the Paso Mallín Chileno which has a road crossing of the border to this day.

The line has not yet been completed. But they are still talking about it and threatening to actually start constructing it some eighty years on. You can read the complete text of the chapter translated in an appendix.(1) Forward from Zapala These sites are apparently no longer available and the political will to progress seems to have expired. The following views showing work ongoing were taken from them. This views shows track laying ongoing on the prepared formation which disappears in the horizon. The labour-intensiveness of the work is readily apparent..

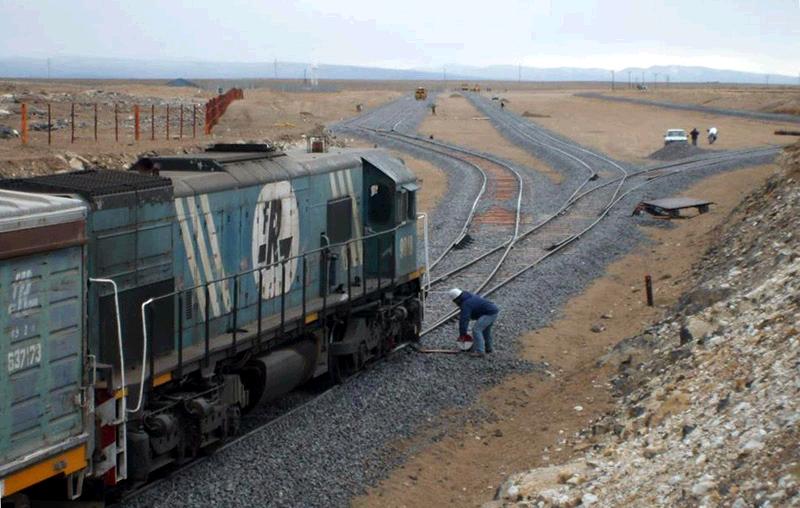

The track has been laid and ballasted with stone; a ballast train has been provided by Ferrosur Roca, taking more stone to where it is needed. The leading vehicle is a 60 ton brake van, a type originally introduced by the FC Sud in the late 1920s. Note how the ballast covers the sleepers.

Here a surfaceman is tightening up the fishplate bolts on the six-bolt US style fishplate. Interestingly the specification called for four bolt fishplates.

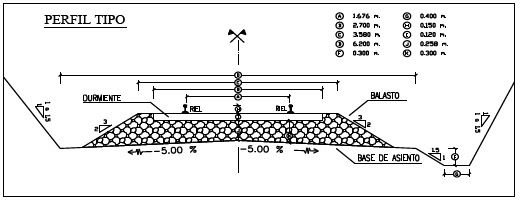

Also evident is the staggering of rail joints. This is done on curves to avoid the periodic use of of slightly shorter rails on curves as was done in the UK. The Argentine practice is for the engineer to determine the difference in length between the inner and outer rail. A standard rail is then cut near the middle so that the difference in length of the two pieces of rail equal that of the length of the two rails round the curve. One of the rails is used at the start of the curve to introduce a stagger to the joints and the other is used at the end on the other rail to bring the joints back in to line. Here the work has reached the media tapada stage where the track has been laid, ballasted, fettled and brought to line and level. The segunda tapada involves laying additional ballast, as shown in the previous view, and ensuring accuracy in the alignment. The government sites gave details of the standards used for the new work some of which are: Below is a cross section of the track in a cutting.

The following photos show the state of play in May 2011. A goods yard has been opened at the western outskirts of Zapala, though there is, as yet, no sign that it has received any freight.

This is a reposting on Facebook by Héctor Guerreiro of a picture in Todo Trenes of a goods train at Zapala Cargas. The track alignment at the throat lacks a bit of fluidity.

From that point onward the line increasingly requires serious earthworks, and it becomes apparent why Zapala has remained the railhead for so long. In this photo it can be seen that the track is ormed of welded rails mounted directly onto quebracho sleepers, with spikes but no baseplates.

Another view at rail height, with the mountains just appearing over the horizon.

After the hundreds of miles of open plain crossed by a train from the east, a cutting like this comes as something of a shock, and makes it very clear why both railway managements and governments have hesitated from completing the final miles to the border.

A view back the other way from the top of the same cutting.

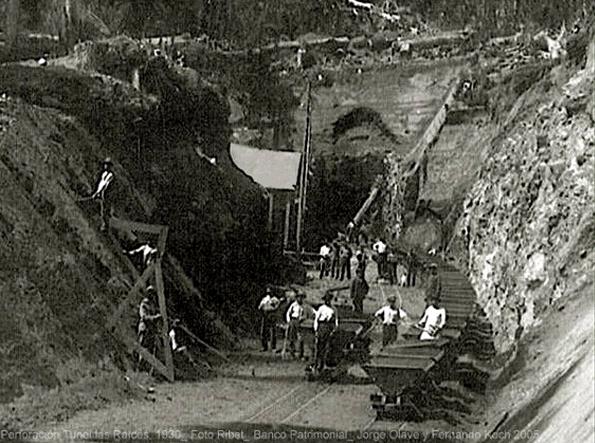

At present, 2015, the earthworks and track do not extend much further than this, at Los Catutos, perhaps ten miles northwest of Zapala. There are no signs of further works in progress, and it would be a brave man who would put his money on a train reaching the border this side of eternity! The concept of the Trasandino Sur, refuses to die. In September 2014, a joint committee of Argentine and Chilean politicians meeting about improving communications with Los Lagos indicated their desire for progress to be made on it (3A). The Chilean end The rather poor photos below show the mouths of the Los Raices tunnel on the branch to Lonquimay that was intended to have linked up with Neuquén had Argentina shown more enthusiasm for the project. Eventually the Chileans gave up waiting and the branch was closed, though it could no doubt be reopened if necessary. The tunnel is now a road tunnel, operating a one-way system at different times of the day, and with notoriously bad air conditions within the single track bore.

The photo above shows a line of skip wagons in one of the approach cuttings, whilst that below shows the other end towards the end of the construction period, with a single temporary narrow gauge track leading into it.

References: 28-1-2018 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

Chapter 3

The BAGSR's route to Neuquén