|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

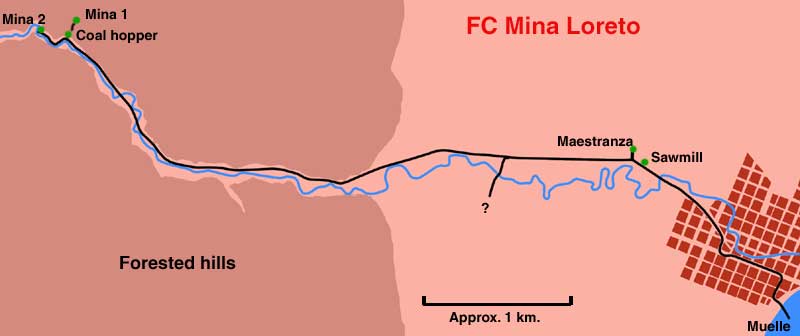

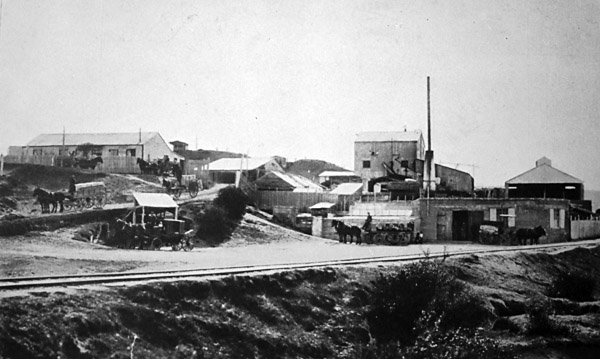

The route of the Mina Loreto line, & relics surviving The line's course is shown on the simplified map below, copied from an original linen plan in the archives of the Instituto de la Patagonia. The post 1902 route is shown. The earlier tramway remained on the north bank of the river for rather longer, only crossing over to run directly into Calle Santiago, the street running diagonally to the rest of the grid pattern.

1

2

3

4 This view can be quite accurately dated to the first fortnight of December 1908. Dr & the second Mme. Jean-Baptiste Charcot arrived in Punta Arenas on board the Pourquoi-Pas? from Buenos Aires. It sailed onward on 16 December for Antarctica. Mme. Charcot is holding a camera. Looking carefully under the coach behind the engine, one can see that it comprises the whole train. I suspect that Dr. Charcot is the man standing on the rails. Presumably, the group of men (and one girl) is made up of senior officers of the ship and their hosts from Punta Arenas. The bowler-hatted man next to the girl seems unusually tall and thus might also be identifiable (3).

5

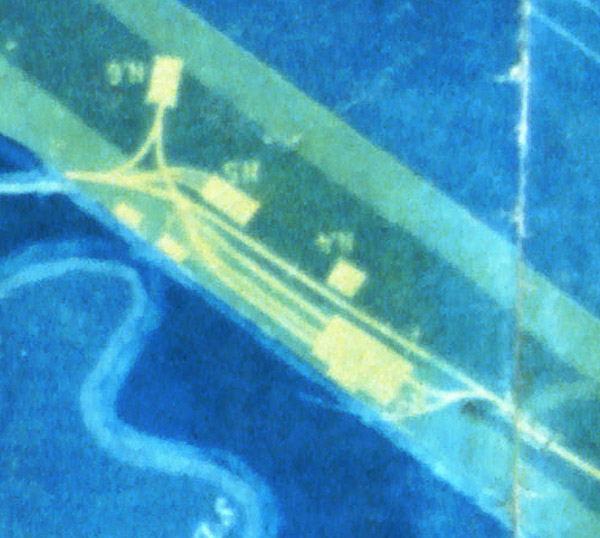

The maestranza complex as seen on the linen plan of the railway held in the archives at the Museo del Recuerdo in Punta Arenas. The original plan was drawn with south at the top, so this cropped extract has been turned through 180 degrees in order to correspond with other maps. The valley of the Río de las Minas is therefore away to the left, and Punta Arenas town is to the right. The railway appears from the mine at the left-hand edge of the map, passes a triangle at the apex of which was supposedly the 'galpón de locomotoras' (loco shed, but see further on), then passes a three road 'galpón de carros' (ie, wagon shed) on the left of the line. A substantial yard has now opened up on the right. This might be the sawmill that was supposed to have been here or alternatively may have been the railway's main workshops. On the opposite side of the line is a small building, labelled as the 'casa mayordomo general' or general manager's house.

6

7

8

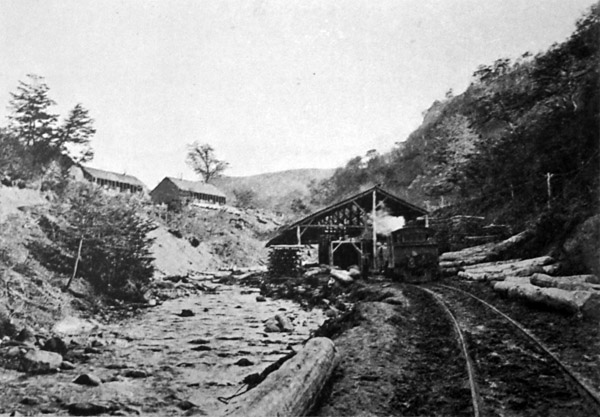

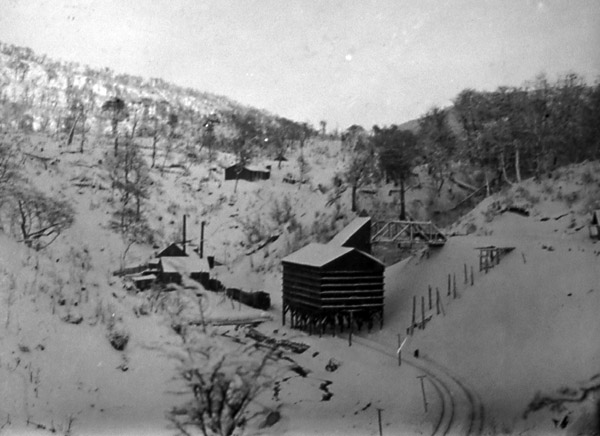

Surviving relics Anyone wishing to visit the old mine sites should be well prepared – both physically and for disappointment. The loose sediments that comprise the valley sides mean that the river is constantly eroding its banks and undermining the river cliffs. The upper course of the railway has largely disappeared therefore, as have any mine buildings. If you should wish to explore take note that the area is part of the National Forest Reserve and that officially you should buy a ticket at one of the forest gates. Take rubber boots to allow wading in the river and avoid the many steep banks; they are very unstable. Further downstream the railway route starts to become apparent near where the line crossed to the south bank and back again. However even beyond here the embankments are not complete. It seems likely that the railway management had to wage constant war against the river even whilst the line was in operation. The photo below was taken looking downstream in the lower valley, after the railway has recrossed to the north bank again. The river is on the right. From where the photographer was standing the track ran dead straight for a couple of hundred yards, passing just to the right of the two bare tree trunks. It will be obvious that the river has taken a great bite out of the alignment just before those same trunks.

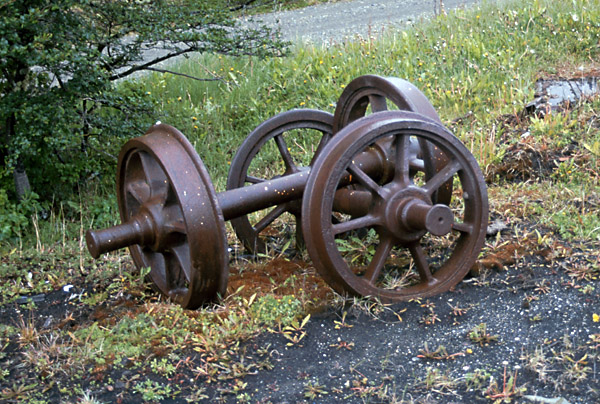

When the river comes out of the valley it now almost immediately enters the outer suburbs of Punta Arenas. Calle Manuel Aguillar up beyond the Barrio Prat area is in fact the actual railway route. There are occasional rails to be encountered as electricity pylons or gateposts but not a lot else. Down in the town centre, Avenida Colón is shaded by a double line of big trees and the old photo of the excursion train is difficult to visualise. The early route through the streets and past the Plaza can still be followed, but again the traffic and high buildings detract from the experience. High in the woods above the valley lie two pairs of metre gauge wagon wheels, obviously from one of the railway's wagons. This is a strange place to find them, for this was not a small mine tub but a fair-sized main line wagon. The coal-black soil suggests that they were brought up here to some sort of mine. They would seem to be the sole surviving relics of the railway's rolling stock. Presumably all else was scrapped in 1950.

Anyone wanting to explore further is invited to contact the author for advice and ideas of locations not yet checked. This is a view looking out along the Muelle Loreto built for the businessman Agustín Ross for the export of coal. It continued in use till about 1940.

Extra photos References 2-2-2018 |

|||||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

Chapter 9

Coal railways including the RFIRT