|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

4 Pichi-Ropulli Osorno report •

9 Branchline station photos 2 •

11 Barros Jarpa Noel agreement ª

Chapter 5

The south end of the Chilean broad gauge

Extending the southern mainline

The mainline south of Pitrufquén, and the route to Valdivia which should be regarded as part of the mainline rather than a branch, were constructed in discrete sections, and not precisely in the logical order from north to south. Rather than wait until the mainline had reached Valdivia, work began from that city and headed towards Osorno on the way to Puerto Montt, the link to the main network only being completed later.

The infamous N&SACCo.

In 1889 a number of substantial railway building contracts were awarded by the Chilean government of José Manuel Balmaceda to a newly-formed American company, the North & South American Construction Company. This short-lived venture seems to have been under-capitalised and under-managed. It soon got into trouble in Chile, and a visiting director, General George Field, was forced to sell the assets and liabilities to Señor Julio Bernstein. The transfer without permission, and the lack of overall progress, offended the government, who eventually expropriated the asssets and sought other means of getting the railways built. The delay led them to begin construction of the southern sections of the Red Sur mainline from Valdivia southward, rather than waiting until the tracks had extended south from Temuco as would have been expected. More detail about the N&SACCo. affair is available in an appendix.

1 From Valdivia inland, and south to Osorno

Government investment in surveys for a railway from Valdivia had been authorised as far back as 1881, whilst a Señor Germán Ebner had investigated the possibility of constructing an independent railway to La Unión and on to Osorno only a couple of years later. Ing. Aurelio Lastarria’s detailed report was published in 1887, showing a route that in all essentials was that eventually built (2).

Construction of this 148 km. section for the EFE seems to have begun in 1890, under the usual Dirección de Obras Públicas supervision. The route was divided into two parts, from Valdivia as far as Pichi-Ropulli, and to that point northward from Osorno. In 1893 the former seems to have been paralizados, as a result of the N&SACCo. collapse, but work was continuing as normal on the southern stretch under a new contractor Manuel Ossa. A report covering Señor Ossa’s work on this section is available in an appendix page.

The railway track out of Osorno to the north ran straight up a main street – Calle Portales – from the station to a bridge crossing the Río Damas on the northern edge of town. This section was later re-routed further west to avoid clashing with road traffic, requiring replacement bridges.

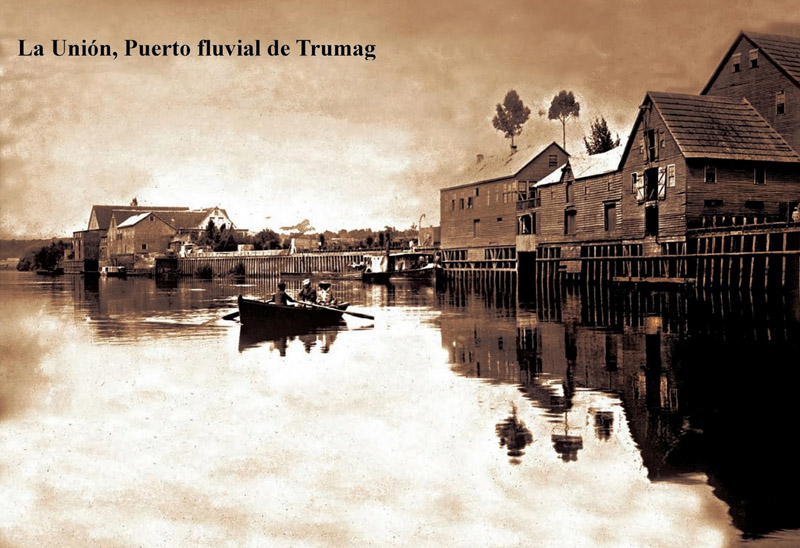

At Trumag – later more commonly called Trumao – there was a good deal of debate about a possible 2 km. branch westward along the southern bank of the Río Bueno to an existing wharf known as Puerto Nuevo. This was surveyed in detail in response to a petition from local businesses, but the frequent flooding along this stretch of the river led to the eventual decision that a new wharf and sidings adjacent to Trumag station would be cheaper and more practicable. The Río Bueno saw a good deal of barge traffic in those days, hence the interest in providing adequate transhipment facilities (3).

The real puzzle, however, is how the locomotives and wagons for the railway contract, and even a pair of passenger coaches, got to Osorno in the first place. The town is 100 km. from Puerto Montt and at that time the rail route between the two had not even been surveyed. Presumably everything was stripped down and transported by horse-drawn wagons before being re-erected at the construction base. Once Trumag had been reached certainly the Río Bueno was used, but in the early stages this would been little better than Puerto Montt as a transhipment point. Whilst such details tend to be ignored in the reports of progress on these new lines, one memoria does record that the Decauville lines employed during the works stretched a total of 27 km. on 60 cm. and 50 cm. gauges, and that they used 300 wagons and 120 mules for haulage (4).

The Río Bueno was a substantial watercourse. As the main text reveals, there was debate about building a branch at Trumag (later Trumao) to link the railway to an existing set of wharves there.

Here is one of the paddle steamers that plied up and down the Río Bueno, though presumably a larger one was used when the first locos for this section of railway were brought up from the coast to Trumag.

By 1894 Adolfo Nicolai had taken over the northern contract and work was well under way, whilst Señor Ossa had already completed his section. Nicolai’s work should have been completed by March 1898 but but was still in progress a year later, though clearly there had been good reasons for the delay as the DOP was not being critical (5). Certainly there had been a couple of deviations from the planned route, so perhaps the earthworks had caused problems. There was also a short tunnel to construct just south of Collilelfu/Los Lagos.

By then the Osorno to La Unión stretch (though not the extension northward to Pichi-Ropulli) had been worked in isolation for three years by the DOP using Baldwin 4-4-0s that had been provided for the construction. There was repeated comment that they, and the rolling stock, were by then in a very poor state, but nevertheless they had covered 64,000 km. without any problems during the previous year. This equates to around two round trips per day, the majority of which were mixtos, with the remainder being ballast trains. Triangles had been installed at both Osorno and La Unión for the locos.

One of the Schneider bridges under construction. This one is at Cuhinco.

The completed length north of La Unión was only being used by the constructor of the line north of Pichi-Ropulli, Señor Nicolai, to bring in materials, but no maintenance was taking place so the track was deteriorating. There were also reportedly problems caused by local people damaging the track and stealing the telegraph wires (6).

By November 1899 the Valdivia to Pichi-Ropulli section had also begun to be worked by the DOP, using four rather worn-out construction locos from this contract, and a fifth from some unknown source. A number of wagons used during construction had been rebuilt as vans for the public service, but owing to the shortage of equipment, just two trains per day each way were being worked right through to Osorno, a passenger and a goods train each taking around 5½ hours, crossing at Pichi-Ropulli. Passenger departures left at 8am from each terminus. Before the railway these journeys took three days. There was considerable criticism about imperfections in the work by Señor Nicolai, and disagreements about payment went to arbitration.

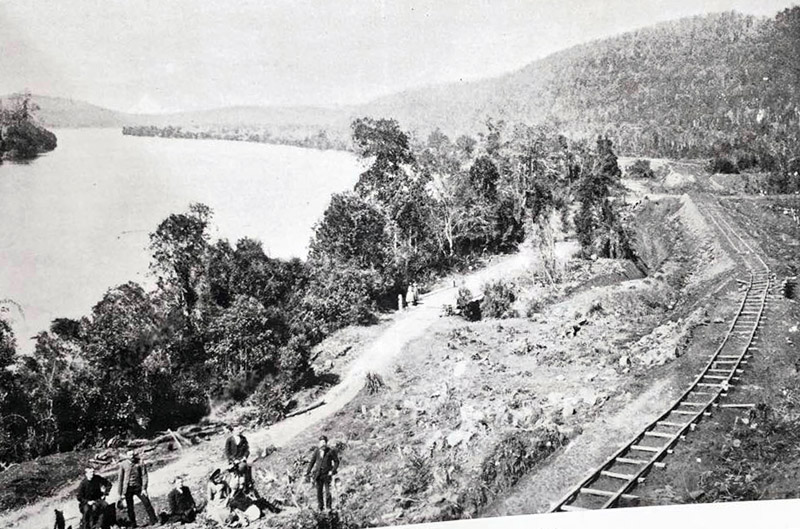

Temporary track is seen here alongside the Río Calle Calle between Antilhue and Valdivia.

A couple of the ex N&SACCo Baldwin 4-4-0s, later to be classified tipo 15 by the EFE, shunt at Huellelhue on the Valdivia to Antilhue riverside section during construction operations. The nearer one has lost its cow-catcher or pilot.

This later postcard, also taken alongside the Río Calle Calle, shows permanent track now in place.

Presumably the expectation will have been that the line from the north would soon arrive at Antilhue, thus enabling new locos and stock to supplement or replace those which were rapidly deteriorating. Complaints about the awful state of them were still being made in 1902 (7). However, the link was not completed until around 1907, by which time the Osorno to La Unión length had been operating for almost ten years. Thirty additional wagons were shipped to Valdivia by sea in 1902 to improve the situation, but there was no sign of any extra locos or coaches. Nevertheless, during that year this isolated railway carried 42,978 passengers and 33,010 tonnes of goods, 2,736 tonnes of this being rails and fixings for the line being constructed north from Antilhue (9). On the 15th May 1903 the operation of the whole line was transferred to the EFE, and it is possible that the new management then took action to provide better equipment.

Valdivia was equipped with a loco shed, workshops, a coal dump, a wagon repair shed, goods sheds, and offices, whilst Antilhue had a coal dump, a goods shed, a loco shed, and staff houses. Along the route goods sheds were provided at Huellelhue, Purei, Collilelfu, Reumen and Paillaco, usually with a small station building. Similar facilities were provided further south, as well as loading ramps for livestock and at Osorno a corral for the animals arriving or departing. Osorno was also provided temporarily with a triangle, eventually replaced by a turntable to make room for a goods yard.

Whilst considering Valdivia it is worth examining other aspects of the city’s situation which were to handicap both it and the railway in the long run. Valdivia is situated on a sheltered ria, a network of flooded river valleys. This gives the city a spectacular backdrop but restricted trade once ships began to get larger, for the only deep water anchorage is off Corral, some 16 km. from the city. Thus transhipment into barges was necessary for goods both inward and outward. The railway station was located on the north-eastern edge of the city, by the river and convenient for this barge traffic but distant from the city centre and even further from industries that began to grow up along its western waterfront.

It is no surprise therefore that there were soon proposals to extend the tracks, into the city centre or out to Corral. Neither came to anything. Whilst the city centre is on a slight eminence, it is not high enough to permit tunnelling without dropping below sea level, something to be wary of so close to the shore. Similarly, getting a railway round to Corral, and to the ironworks still to be covered in Chapter 13, would have required the bridging of several wide and marshy river valleys and could not have been achieved without a tortuous and therefore lengthy route. The failure to build either of these two extensions did however have an interesting consequence. Shipyards at Valdivia, notably the Astillero Behrens, developed a profitable sideline in railway wagon construction. Since the yards were not connected to the mainline, the finished products had to be shipped by barge up the Río Calle-Calle before being unloaded onto the tracks at Valdivia station. A single rail survives on Calle General Lagos, showing where a shipyard’s internal broad gauge tracks once crossed the road.

2 Between Pitrufquén and Antilhue

Work on the 114 km. of route required to link the newly-completed Valdivia to Osorno railway to the remainder of the broad gauge network began in 1899, when the contractor Eugenio Bobillier was awarded both of the original N&SACCo contracts – 64.6 km. from Pitrufquén south to Loncoche, and a further 50 km. from Loncoche on to a new junction with the Valdivia line at Antilhue.

The latter task included the construction of a 180 m. three span viaduct over the Río Calle-Calle just north of Antilhue. All of these railway building projects in the south of Chile involved extensive bridge building, for the rainfall is high and the substantial rivers can get even bigger in flood times. The usual procedure was to construct temporary timber trestles so that access could be gained to the opposite bank. Then the abutments and piers were built, originally in masonry but by this time mass concrete was taking its place, not least because finding good stone in the south had proven difficult. In the case of the Antilhue viaduct the two central piers were to be constructed using compressed air, but it was found necessary to dig much deeper than had been expected in order to find a solid foundation, and the compressors were inadequate for the task. This was one of the causes of delay to the completion of the route, construction of a nearby embankment and flood relief bridge across the floodplain also being delayed until the completion of the main river bridge in order that floodwaters not be concentrated against the temporary wooden trestle.

Once the preparatory work had been completed, steel trusses were erected on top. Much of the steelwork was fabricated by Schneider & Co. of Le Creusot in France, but such was the state of their order-book that the temporary wooden structures often carried the public service for a year or two before replacement.

In 1902 it was reported that Bobillier was using three 4-4-0s on the northern contract, and three tank locos further south. The former included the Baldwin 4-4-0 No. 3520 of 1874, ‘LINARES’, which spent many years as a DOP hire loco, and a ‘TALAGANTE’, one of the ex=N&SACCO. Baldwins. Of the tanks, two were employed north of the Calle-Calle bridge and the last on the short section between that structure and the existing railway at Antilhue (10).

At the end of 1903, it was anticipated that both contracts would have been largely completed by the end of 1904, though several large rivers would still be crossed on temporary spans. The Calle-Calle bridge was the only part that was expected to take longer, possibly being finished by May 1905. In 1904 the EFE had introduced a 4th operating division of the Red Sur, from Victoria southward, so presumably a quick completion was anticipated.

In fact the Pitrufquén to Antilhue route was provisionally received from the contractor on 19 and 20 March 1905, but the bridge may not have been finished until 1907. However, an interim train service had started: one train per week each way (11). Once the Afquintué tunnel had been finished then this was to be increased to six trains per week, three each way. Presumably these ran right through, utilising the temporary trestle to bypass the Calle-Calle viaduct.

3 Osorno to Puerto Montt

When Osorno had been joined to the main national network serious work could begin on the final stretch of the southern mainline, the 126 km. from there to Puerto Montt. Surveys had been conducted in 1901, whilst the detailed drawings were ready by 1906. In June 1907 the main contract was awarded to Señor Pedro A. Rosselot, though sadly he himself died during the construction period, with responsibility then passing to his widow, Doña Berenice Aravena (12).

The biggest single task was not in fact a part of the railway itself but the 1100 m. wharf at Puerto Montt, which required 19,000 m3 of concrete. However, there were also 18 major metal bridges to build, several of which were delayed owing to serious floods in 1910. Nevertheless, by the end of that year 36 km. of permanent track had been laid from Puerto Montt and 42 km. from Osorno. A shortage of sleepers was reported to be delaying matters.

Señor Rosselot took delivery in 1908 of four new broad gauge 4-4-0s built by Lima in the USA. Since the names of these included ‘CHAHUILCO’ (No. 3) and ‘LLANQUIHUE’ (No. 4) – both locations along the Puerto Montt extension – it seems highly likely that the batch were intended for use during this contract. In addition No. 1 ‘QUEPE’ has gone down in Puerto Montt history as the very first locomotive to enter the town. Four further Lima 4-4-0s, of a slightly larger size, arrived in 1910, probably also for use here. All eight engines were sold to the EFE from 1914 onward, becoming their tipos 62 and 63 (13).

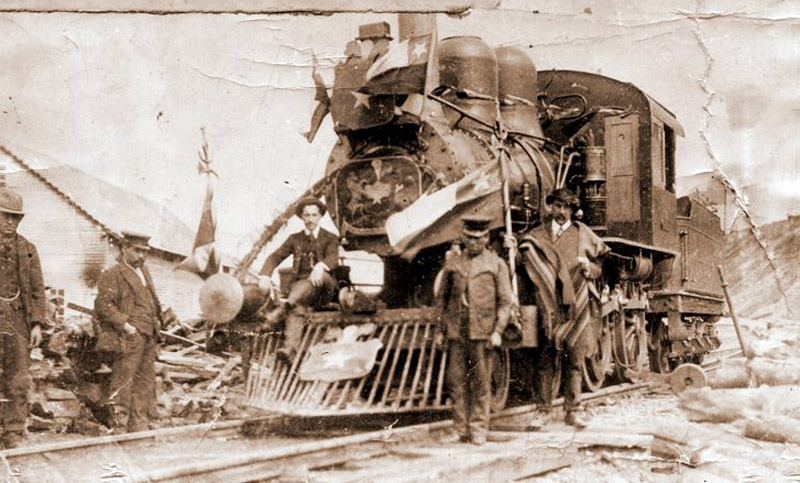

The 4-4-0 loco ‘QUEPE’, one of Señor Rosselot’s purchases from Lima of Ohio, was the first engine to be unloaded at Puerto Montt, and has gone down in the town’s history for that reason.

One of these Lima 4-4-0s is seen here on a construction train in one of the new stations.

By August 1912 most of the work had been completed and the track was sufficiently lined and ballasted for a weekly train to be run in each direction, presumably headed by one of the 4-4-0s or by the DOP’s 2-6-0 No. 3 (Borsig 6010 of 1906) which was seemingly the only loco hired out for this contract. The DOP annual report to Congress that year clearly illustrated some of the problems of the interim service on a new railway:

“The passenger train service could not be run well, despite the excellent condition of the track; it was difficult to avoid accidents, in the first place because of the inadequacy and poor quality of the rolling stock, and secondly by the malevolence of the neighbours who destroy the fences, thus making possible the entry of cows onto the track. This last circumstance has been the cause of almost all the derailments, happily without there having been any injuries.

With regard to the cars, they are old and rotten, so that the sparks that come from the locomotive penetrate easily in the crevices and cause frequent fires, resulting in long delays and serious danger to the safety of passengers. To run a good service would require at least four coaches of good quality.” (14).

More seriously a collision in February 1913, between an inspection train and a ballast train south of Río Negro, led to two fatalities. The contractor was to blame, the ballast train being in section without permission.

The full opening seems to have been a few months later, for “Today at 9am departed the first goods train, that will run every other day between this town and Osorno. According to the schedule the train will depart Puerto Montt on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, and will return on Sunday, Wednesday and Friday of each week.” as El Llanquihue of Puerto Montt reported on 20th May of that year.

Passengers on the first train into Puerto Montt in 1913 pose for a photo behind their special train.

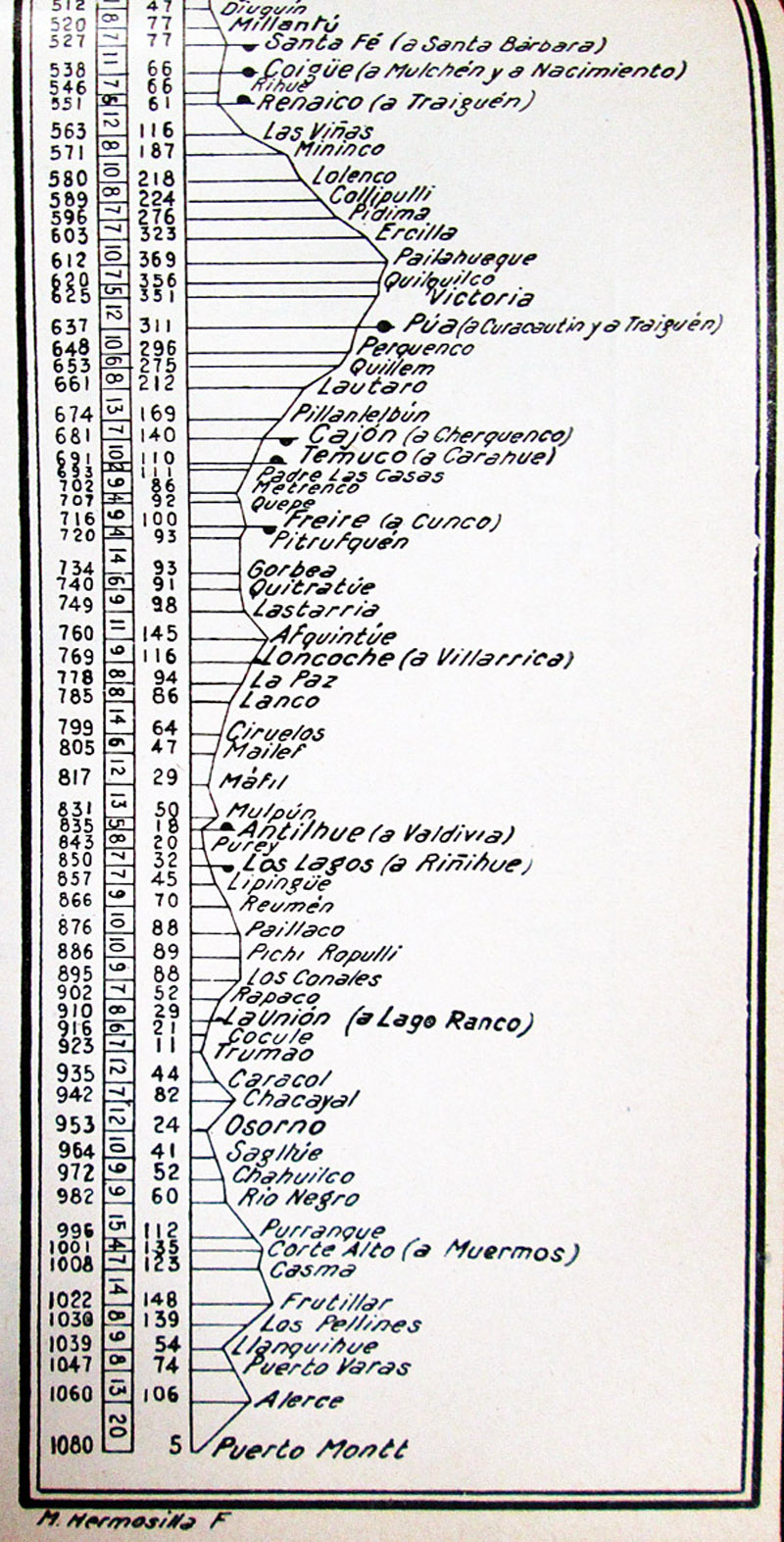

A section of the Red Sur mainline gradient profile, from near Santa Fe southwards through Victoria and onward to Puerto Montt. The three columns of numerals on the left show: kilometres from Santiago, gradients per thousand, and heights above sea level.

References

1 Advisory report on the state and prospects of the railway, 1909, p8, in ArNAd volume MOBR2332. ArNAd = the Chilean Archivo Nacional de la Administración, at Avenida Matucana 151 in Santiago.

2 Santiago Marín Vicuña, 1916, Los Ferrocarriles de Chile, Imprenta Cervantes, Santiago, p91. Available online at http://www.memoriachilena.cl/temas/documento_detalle.asp?id=MC0057501

3 http://loslagoshistoriaypoesia.blogspot.com/2011_05_01_archive.html

4 Leopoldo E. Guillén, Monografía de los ferrocarriles de Chile, 1939. p40.

5 Various items of correspondence from 1908-9 contained in ArNAd volume MOBR1834.

6 ArNAd volume MOBR2332.

7 Decreto 105, 20 January 1911, in ArNAd volume MOBR2332, p96.

8 At this point the concession was transferred yet again, this time to the Sociedad Anónima Transandino por San Martín.

9 Leopoldo E. Guillén, 1939, Los Ferrocarriles de Chile. Monografía. Extracto de la Monografía de los Ferrocarriles de Chile, Santiago de Chile.

10 Inventory 1909 contained in ArNAd volume MOBR2332; Estadística volumes; and in W. Rodney Long, 1930, Railways of South America: Part 3: Chile, U.S. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce - Trade Promotion Series No. 93, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.

11 Santiago Marín Vicuña, 1916, Op. cit., p95.

12 W. Rodney Long, 1930, Op.cit.

13 Estadística de los ferrocarriles en explotación, 1927, Santiago.

14 W. Rodney Long, 1930, Op.cit.

11-3-2018