|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Main pages

Appendices

4 Pichi-Ropulli Osorno report •

9 Branchline station photos 2 •

11 Barros Jarpa Noel agreement ª

Chapter 5

The south end of the Chilean broad gauge

The later history of the Los Lagos to Riñihue metre gauge branch

The earlier history of this line as an independent railway is covered on the previous page.

ISuccessive takeovers

In 1928 the railway was taken over by the new Compañía Electro-Siderurgica e Industrial de Valdivia – ESVal – who also now owned the Altos Hornos steelworks at Corral west of Valdivia, covered in Chapter 14 (1). More relevantly, they were the promoters of a Lanco to Guahun (= Huahun or Huahum) Pass broad gauge electric railway, which would have started from the Red Sur mainline at Lanco, almost 50 km. further north. This would have run south-east to Panguipulli on the alignment later used by an EFE branch, and then followed the same strategy as the earlier San Martín scheme, in fact along the same alignment from Puerto Fuy onward. Hydro-electric power was to have been generated from the Huilo-Huilo falls.

The company’s purchase of the Los Lagos to Riñihue railway led to speculation that the scheme would be revised to utilise the existing trackbed. However, nothing came of the new proposals, and in 1936 the Riñihue line was again offered to the state railways, perhaps implying that the new owners had also given up their international ambitions. This time the offer was accepted, and seemingly at the price the company had asked for. This then became an agreed expropriation by the government, possibly for legal reasons (2). The necessary decrees were issued in May 1937 but in fact the takeover by the EFE did not take place until late 1942, perhaps owing to delays in raising the necessary funds. In the meantime there seems to have been little change in the day-to-day operation of the line, though the 1940 summer timetable was down to five passenger trains per week, taking roughly 2½ hours each way.

Takeover by the EFE, however, certainly led to changes on the motive power front, not surprisingly after over thirty years with the original small locos. Nevertheless those were incorporated in the EFE fleet, with the new numbers of 3118-20, and classified in tipo C, which seems to have been something of a catch-all class for miscellaneous small engines since it also encompassed some ALCo Cooke 0-6-0Ts from the Arica-La Paz railway and a Neilson 2-4-0T which originated with the contractor Matheson & Co. of Iquique (3).

Most of Chile’s metre gauge lies in the northern parts of the country, made up of the EFE’s Red Norte and a number of other railways which have been independent for at least parts of their lives. These include the FC Antofagasta a Bolivia – still very much in operation today, the FC Arica-La Paz, and of course the spectacular and much-missed FC Trasandino Chileno. The isolated metric branches in the south, including also the line from Talca down to Constitución on the coast, therefore tended in later years to be supplied with cast-offs from the north.

The Red Sur working timetables listed running numbers for the metre gauge locomotives transferred south and in the charge of Concepción works, but they did not specify precisely which of the southern lines they were allocated to; thus we have to combine this information with an independent report giving 1954 data about which classes operated from Los Lagos in order to get a reasonably complete picture (4). It then becomes clear that a number of much larger locomotives were brought in by the EFE, probably with the intention of operating fewer, though longer, trains and thus making economies.

At least two of the Rogers 2-8-0s of tipo R arrived, along with a Henschel 2-6-0 of tipo Q. Subsequently, perhaps even as late as the 1960s, a type W 2-8-2 was introduced, one of a few brought down from the north as dieselisation proceeded in the Atacama. This last was an enormous machine by the previous standards of this branch, and must have stretched the capabilities even of the relayed track to their limits. Finally, on a smaller scale, a tipo D loco appears on the list, presumably Rogers 5189 of 1878 which had begun life as a 2-4-0 and then been rebuilt with a trailing truck as a 2-4-2T.

The original tank locomotives had run on wood fuel, no doubt purchased locally, but after the takeover coal became the main source of energy, wood perhaps being less suitable for the larger locos.

The table on page 138 shows that there were three passenger coaches in the fleet in 1954, together with one furgón. These may well have been from the original FCTpSM fleet, but new wagons must have been brought in after 1942 as the total was up to 36. Interestingly, the majority of these seem to have been out of use by the mid 1950s, though that may merely indicate that older pre-EFE wagons had not yet been scrapped (5).

Tommy Farr took three photos of locos lying derelict at Los Lagos after the closure. The first shows Henschel tipo Q 2-6-0 no. 3076.

The second illustrates tipo P 2-6-0 no. 3227 built by Borsig in

Tipo R 2-8-0 no. 3087, or the type original known as ‘Consolidada Calera’, eventually ended up on this railway but has since been preserved.

There is no proof that a tipo W 2-8-2 ran on this line, but one source suggests that this was the case.

The railway in the 1950s

Examination of the railway after the state takeover is aided enormously by a study undertaken in the mid-1950s by a civil engineering student at the Universidad de Chile. Engineering students were required to research and write up a substantial final dissertation as part of the requirements for the award of the title Ingeniero, which in Chile as in Argentina carries the status which we would accord to the title ‘Doctor’. Clearly one of the professors in the faculty at the time must have been in the habit of suggesting that the possible improvement of one of the EFE branch lines would make a good topic, for the university’s mathematics & physical sciences library contains several such works from that decade. That presented by Señor René Katz Siebrecht in 1956 studies the operations and prospects for the Los Lagos to Riñihue branch in some detail and much of the following data was obtained from this source, which clearly had been prepared using unpublished EFE documents (6).

Taking the infrastructure first, in 1954 two thirds of the route was still laid in the 20 kg./m. (= 40 lb./yard) rail originally purchased around 1908; whilst the remaining third had been relaid in 30 kg./m. (60 lb./yard) rail. The relaying had been undertaken as and where was most urgent, rather than systematically from one point. It seems likely that this re-railing was still under way and that it will eventually have been completed along the whole route.

At the time when Señor Katz was writing, the branch was utilising 31 track workers under an inspector. The report commented that this number was extremely high for only 40 km. of single track and that it was principally due to the very poor state of the alignment and of the track itself. No doubt this was true after a poor start, probably thirty years of minimal maintenance, and then the introduction of much heavier locos and stock. Perhaps the tipo Q and the pair of Rs were forgiving, but by the time that the big tipo W 2-8-2 arrived it seems likely that the route would have had to have been in the heavier rail throughout.

In addition it seems that the minor bridges, originally constructed in timber, were being rebuilt in concrete and steel. Certainly sets of surviving abutments listed as being of timber pile construction in 1954 are now in concrete. Most of the buildings had also been framed in wood and by the ’50s were “francamente malo”! A new station building was erected at Riñihue, and possibly there was some rebuilding at Los Lagos, though none of that now survives. The original Collilelfu headquarters – half a mile from the junction – was almost certainly closed soon after the takeover, for it does not appear in any of the EFE lists of stations on the route.

There were no radical alterations in the patterns of traffic on the line. The graph above right shows that there continued to be much more outbound goods traffic than inbound and unsurprisingly that it was largely loaded at the three manned stations of Folilco, Huidif and Riñihue, and transhipped to the broad gauge for onward haulage elsewhere. 85% of it was timber heading to Santiago or Valdivia, with wheat making up the next largest single freight. Los Lagos does not appear on the graphs as traffic originating there was largely for the broad gauge and in any case the statistics for that station do not distinguish between broad and narrow gauge destinations.

EFE tables of passenger figures are most often organised by the originating station, as in graph 6.6 below, and only rarely show the destination stations. In the case of the branch this makes very little difference as most journeys were to Los Lagos and the return journey pattern is likely to have been be almost identical. On average around 10% of passengers travelled first class, with the remainder making do with 3rd class accommodation.

At the bottom of the previous page is a graph (6.7) of the annual freight and passenger totals for whichever years are available between 1926 and 1970. Passenger traffic has clearly built up since the 1930s, and in the ’50s was still rising. Goods on the other hand seems to have varied a good deal from year to year and was roughly comparable with the 1936 figure.

It would be easy to fall into a trap of thinking that because traffic levels in the 1950s were reasonably stable that the line was still broadly breaking even. However, this was by no means the case. Señor Katz Siebrecht was permitted to study EFE figures analysing the annual tonne-kilometres and passenger-kilometres of traffic originating on this line in comparison with the Red Sur and Red Norte networks as a whole:

It is clear from this that the branch was creating considerably less traffic per kilometre than the average for the Red Norte, which itself was regarded as an unprofitable but socially necessary system, and only 3-10% of the traffic levels created on the Red Sur as a whole. This on its own might not be important, but if the branch were to be making a financial loss then clearly the figures above would tend to suggest that closure could take place without much loss of traffic on the rest of the network.

Moving on to income and expenditure, and cutting a long story very short, the total costs of operating the line during 1954 amounted to 31,909,443 Chilean pesos. The income from the branch, on the other hand, was only 5,659,660 pesos. This gives an operating ratio (expenditure divided by income) of 563%, and still as high as 357% even if indirect costs such as the branch’s share of central administrative costs are discounted. This was obviously highly unsatisfactory, but it is difficult to see what the EFE could have done about it. In the short term the improvement of the track to permit the operation of fewer longer trains was costing a good deal, and in the longer term the improvement of local roads was likely to reduce traffic as alternative means of transport attracted customers away from rail. It seems likely that already the timber traffic from further east, brought to Riñihue by ship, had largely been lost as roads had been constructed around the lake.

Whilst on this topic, it is worth considering the problems that the break of gauge at Los Lagos caused. These can be divided into two parts: goods transhipment problems, and railway operating difficulties. Goods, which mostly were outbound timber and agricultural products destined for Valdivia or elsewhere, were delayed, and suffered deterioration owing to the man-handling necessary at the junction and losses through carelessness or theft. In addition a transhipment charge was levied, which could be as high as 12% of the normal distance-based tariff for something like wheat heading to Valdivia. This paid for daily contract workers who were hired as necessary to move goods to and from the narrow gauge wagons.

For passengers there were no such difficulties, the branch trains being timed to coincide with mainline connections and the cross-platform interchange being no more onerous than from any broad gauge branch. In any case few of the passengers on the line travelled further than Los Lagos.

For the EFE, however, the gauge difference required that a separate workshop be provided for the metre gauge locos and stock, and of course prevented the efficient use of spare equipment elsewhere in the area. Items needing overhaul at the maestranza in Concepción also required loading onto broad gauge wagons, and sometimes this could only be done after after an initial strip-down so that the loading gauge would not be fouled.

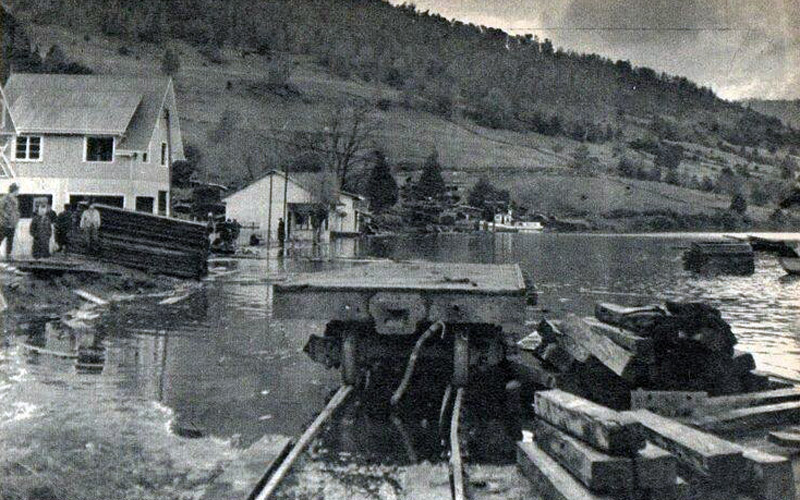

A view down the slip at Riñihue.

Operations under EFE ownership

The principal change in operating terms seems to have been that instead of a pattern of passenger and mixed trains with no separate freights, there were now cargas (goods trains) and mixtos, with no separate trains solely for passengers. This may reflect a change in the relative importance of passenger and goods traffic, or may merely have resulted from the newly-arrived EFE tender engines being able to haul longer trains than would have operated if the passenger stock was used on its own.

In the mid-1950s there were still roughly sixteen round trips per week along the line, with the tipo Q 2-6-0 usually being used on the daily mixto and the tipo Rs on the goods. The mixed trains were normally made up of three coaches (two 3rd class vehicles and one 1st/3rd composite), a furgón brake van and one goods vehicle which may well have been a covered bodega or boxcar. These trains normally took around 2 hours 20 minutes for a single journey, whilst no doubt the freights shunted at intermediate stations with little sense of urgency.

Of the stations and paraderos, only Los Lagos, Folilco, Huidif and Riñihue were manned. Folilco and Huidif in each case solely by a Jefe de Estación who fulfilled the multiple roles of ticket clerk, signalman, telefonista etc. The other, unmanned, stopping places only dealt with goods paid for in advance, whilst the guard carried a book of tickets for passengers joining trains there.

The bridge at Collilelfu / Los Lagos, looking east.

Riñihue station was flooded during El Riñihuazo, after the earthquake of 1960.

Decline and closure

We never again find such detailed data about the railway as had appeared in Señor Katz’s dissertation, but station-specific traffic figures for some of the later years appeared in the memorias anuales of the EFE, though not in every issue. A glance again at graph 6.7 will show that goods traffic was clearly in catastrophic decline after 1960, being down to 17,728 tonnes in 1965, 13,326 in 1968, and 4,908 tonnes in 1970. This should be no surprise; the steady improvements in public roads, mentioned towards the end of Chapter 5, applied here too and with additional force given the transhipment delays and costs at Los Lagos that could be avoided if lorry-load traffic continued all the way to Valdivia.

The passenger figures do not seem to have declined in the same way, though the presence of a parallel route along the whole length of the railway no doubt facilitated the growth of bus services particularly once the road had been surfaced. Perhaps the nature of the passenger flows – directed almost entirely towards Los Lagos and therefore with no transhipment to be avoided – tended to keep the customers using the railway for as long as it was available.

The same political reluctance to face up to closure kept the line operating right through the 1960s, but as in the cases of the broad gauge branches, General Pinochet’s military government took advantage of its relative independence from public pressure to make a decision in favour of closure. In the case of this particular route the announcement came in 1975, several years before the more general removal of subsidies, which may well imply that the Riñihue branch was even more severely in the red than the others.

What’s left of the railway?

There is little to be seen at Los Lagos station, but a short stroll south and around the first curve to the east brings a visitor to a water tower and then to the big single span bridge across the Río Collilelfu. This now carries pedestrians into the town centre. Across the concrete features of what is now the town square can be seen a dirt road and following this takes one past the rather decrepit Collilelfu station building, the headquarters of the railway’s original owners. The significance of this has been recognized and it has been granted the equivalent of ‘listed building’ status. The trackbed then continues past the town bus station and starts to climb out of the urban area, with part of it now surfaced as Calle Conductor Núnez – perhaps named after one of the railway’s loco drivers?

The Río Collilelfu bridge is now a footbridge linking parts of the town of Los Lagos.

The majority of the route onward toward Riñihue lies parallel to and on the south side of the now tarmacked road, the principal part not visible being the decline down to and ascent up from the Río Quinchilca bridge. Much of the latter has now disappeared, probably owing to river erosion. Many smaller bridge abutments survive, as do loading bay platforms, for example at Huidif. A number of houses, chicken runs and barns now stand on the railway alignment, perhaps because the raised embankments provide dry sites which minimise flood risks.

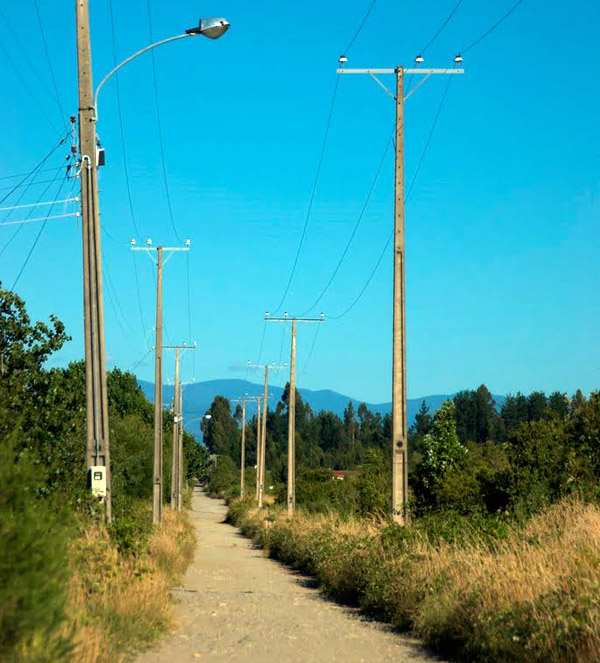

The old trackbed leading out of Los Lagos, as seen in a photo by an unknown photographer.

After the site of Paradero Piedras Moras the railway broke away south from the road in order to find a more gentle route down to the lakeside terminus, returning back across the valley on a substantial embankment to cross the main road and enter the Riñihue station site parallel to the lake shore. This lies below the single street containing the police station and shops of Riñihue village and still displays the roofless shell of the EFE’s replacement station building. The station nameboard also survives adjacent to the old level crossing, but there is no sign of the jetty. Interestingly, the station site points north but the original Trans-Andine proposal would have eventually required an alignment running around the southern shore of the lake. Whether there would have been a reversal here, or a new alignment down the hillside and away south-eastward will probably never be known.

The railway’s steamer Riñihue, as renamed Enco and later abandoned on Lago ???. Photograph ‘El Enco’ by Eira Sanchez in the Wikimedia Commons collection.

The tipo R Rogers 2-8-0 no. 3087, which was used on this line, is now displayed in the Parque Quinta Normal museum in Santiago.

References

1 W. Rodney Long, 1930, Op.cit., p163.

2 Carlos Huidobro Díaz, 1939, Op. cit. p215; and correspondence in ArNAd volume MOBR 4095.

3 Ministerio de Transportes memoria anual for 1943, p142.

4 René Katz Siebrecht, Estudio del mejoramiento del FFCC de Los Lagos a Riñihue, Memoria de Prueba para optar al título de Ingeniero Civil de la Universidad de Chile, 1956. Copy in the Biblioteca Central, Facultad de Ciencias Físicas y Matemáticas, Universidad de Chile.

5 René Katz Siebrecht, ibid, 1956, p61.

6 René Katz Siebrecht, ibid, 1956.

11-3-2018

|

??? |